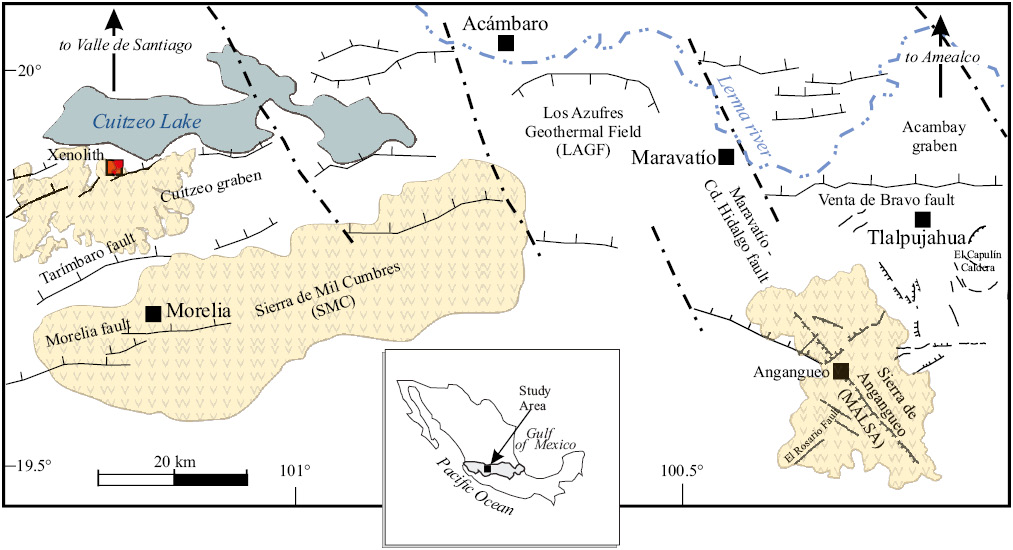

Figure 1. Location map of the Cuitzeo area showing the fault segments in the Morelia-Acambay fault system; Sierra de Mil Cumbres (SMC) and Sierra de Angangueo (MALSA) Miocene andesite-dacite-rhyolite sequences (“v” dashed yellow); and the main localities in the study area. Note three NNW–SSE large and extensional tectonic lineaments disrupting Miocene andesitic ranges, which are also separated by resurgence of the Los Azufres Geothermal Field (LAGF). (After Pasquarè et al. (1991), Garduño-Monroy et al.(2009), Gómez-Vasconcelos et al.(2015), Hernández-Bernal et al.(2016)). (Inset) Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (TMVB) and the Michoacán-Guanajuato Volcanic Field (MGVF) in Central México. Red square location of main study area.

GEOLOGY OF THE CUITZEO IGNIMBRITE (Czi-16.88 Ma)

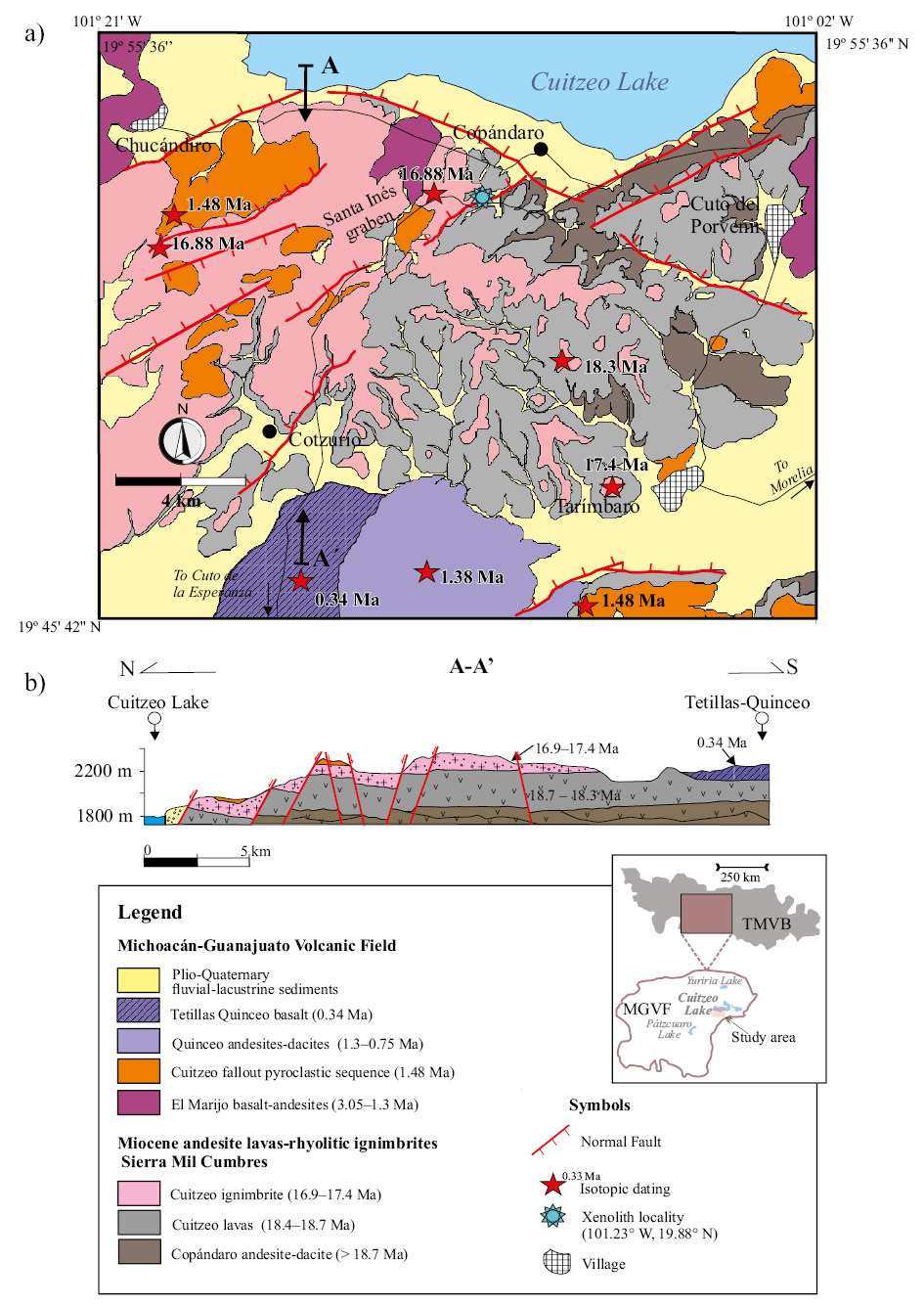

A thick exposure of the Early Miocene Sierra de Mil Cumbres (SMC) volcanic sequence, occurs along the southern margin of the Cuitzeo region (Figure 2). This package consists of interbedded lava flows and ignimbrites (Gómez-Vasconcelos et al., 2015), which were grouped into three main units: (i) the Copándaro andesite-dacite lavas (>18.7 Ma), (ii) Tarímbaro andesite-dacite lavas (18.3–18.7 Ma), and (iii) the Chucándiro ignimbrite (16.7–17.4 Ma) (Trujillo-Hernández, 2017). Late Miocene and Pliocene units are represented by 8.11–3.02 Ma basalt-andesite lavas. Quaternary units belonging to the Michoacán-Guanajuato Volcanic Field (MGVF) discordantly cover the Early Miocene rocks. Among them, we highlight the Cuitzeo pyroclastic fallout (Czf) marker (1.48 Ma), the Quinceo small-shield unit (1.36–1.37 Ma), and the Tetillas small-shield unit (0.56 Ma). All volcanic units are surrounded by fluvio‐lacustrine deposits (Trujillo-Hernández, 2017; Avellán et al., 2020).

According to Pola et al. (2016) and Avellán et al. (2020), the Tarímbaro unit correlates with the Cuitzeo lavas (Czl) and the Chucándiro ignimbrite correlates with the Cuitzeo ignimbrite, both of them mapped in a region further south. Therefore, we will refer to the Cuitzeo lavas (Czl) and Cuitzeo Ignimbrite (Czi), accordingly.

The Czi was deposited between the Czl and the Czf units (Figure 2). The distribution of the Czi unit suggests that it was probably originated from a caldera located north of the study area (Trujillo-Hernández, 2017). The Czi is a white to pink massive welded ignimbrite with a fine ash matrix. The geological mapping made by Pola et al. (2016), Trujillo-Hernández (2017) and Avellán et al. (2020) show some slight differences between them but they agree with the age and general features. These authors describe up to ten different lithofacies, based on texture, components proportion, welding, and degree of hydrothermal alteration. Lithofacies are prevalently stratified, but some lithofacies are composed of an alternation of massive and stratified poorly consolidated layers (Pola et al., 2016). The Cuitzeo ignimbrites are composed of different proportions of pumice and lithic lava fragments within a fine-rich altered matrix composed of glass, lithics, plagioclase, quartz, amphiboles, and oxides crystal fragments, and large amounts of montmorillonite.

Granitic xenoliths were found at the base of the Czi (Trujillo-Hernández, 2017), within a moderately welded matrix-supported pink lapilli tuff. This lithofacies contains subrounded pumice clasts, abundant quartz crystals and angular accessory lithics, including red and black lava fragments, besides the granitic xenoliths. A phenocryst-free whole rock ignimbrite sample dated by Ar-Ar on an outcrop of Czi near the studied site shows an age of 16.88 ± 0.22 Ma (Trujillo-Hernández, 2017).

Figure 2. a) Map showing the geological units in Cuitzeo region, the location of geochronological (red stars) data and the location of the granite xenolith used in this study (circle star). b) Cross-section A-Aʼ showing the main stratigraphic and structural features. Due to the scale, Plio-Quaternary lacustrine sediments are not shown in this cross-section. (After Pasquarè et al.(1991), Trujillo-Hernández (2017), Avellán et al.(2020)).

ANALYTICAL PROCEDURES

Approximately 200 g of fresh sample material of one granitic xenolith were crushed in a jawbreaker, agate mortar, split into aliquots, and finally pulverized with a tungsten carbide mill set for geochemical and isotope analyses. Major elements were determined by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) using a Siemens SRS-3000 instrument at the Laboratorio Nacional de Geoquímica y Mineralogía (LANGEM at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México -UNAM-). Trace element abundances were obtained by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) at the Centro de Geociencias (CGEO-UNAM), using a Thermo Series XII instrument of the Laboratorio de Estudios Isotópicos (LEI). The Sr–Nd isotope analysis were performed with a Finnigan MAT 262 thermal ionization mass spectrometer at the Laboratorio Universitario de Geoquímica Isotópica (LUGIS-UNAM). The zircon crystals were analyzed at the laser ablation system facility of the Laboratorio de Estudios Isotópicos (LEI-CGEO-UNAM), by employing a Resonetics M050 excimer laser coupled with a Thermo Xseries quadrupole ICP-MS. Quantitative electron-microprobe analyses were done with a JEOL JXA-8200 electron microprobe working on wavelength-dispersion mode, at the Department of Earth Sciences of the University of Milan (ESD-MI).

Pressure-temperature (P-T) and physical conditions were estimated using amphibole, plagioclase- amphibole pairs and Ti-in- zircon electron microprobe and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analyses (Table 1). Microsoft® Visual Basic software WinAmptb (Yavuz and Döner, 2017) was used to calculate the pressure (P), temperature (T) and oxygen fugacity (ƒO2) conditions of amphibole and amphibole-plagioclase pairs of granite rock. Pressure calculation was carried out using the Al-in-hornblende barometry formulation by Mutch et al. (2016). Crystallization temperature was successively checked from pressure-dependent expressions of Anderson et al. (2008) using pressures obtained from Mutch et al. (2016).

RESULTS

Petrography and mineral chemistry of the Granitic Xenolith of Cuitzeo

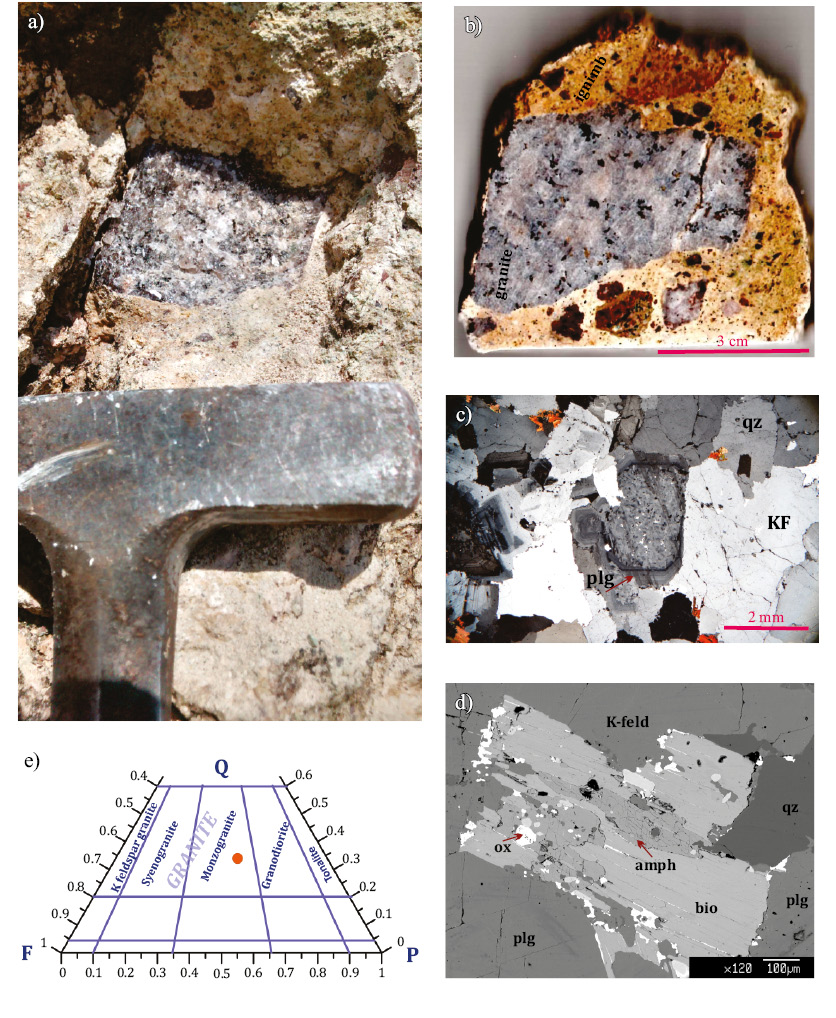

Xenoliths within the 16.88 Ma Cuitzeo reddish-pink welded ignimbrite (Czi) are abundant, angular to subangular and square shaped, fresh pink, granitic fragments ranging from 1 to 10 cm in diameter (Figure 3a, 3b). Ignimbrite-xenolith contacts show no thermal, or chemical effects, or reaction zones. Granitic xenoliths contain abundant medium to coarse K-feldspar, quartz, plagioclase, biotite, and amphibole crystals. The phaneritic texture of the xenoliths contrasts with the reddish-pink pyroclastic host, where aphanitic lithics and pumice fragments range between 2 and 10 cm.

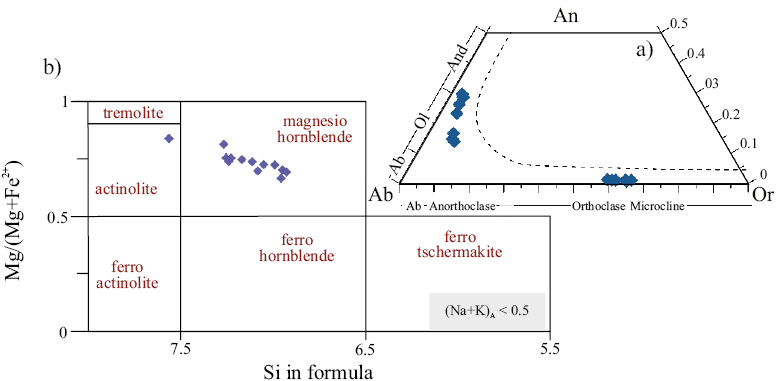

For petrography and mineral chemistry characterization we describe and analyze only one sample. It is a leucocratic, phaneritic, 4 cm wide by 5 cm long rock with a noticeable oxidized border. Petrographically, the studied sample comprises plagioclase (35 vol. %), quartz (30 vol. %), K-feldspars (25 vol. %) and 10 vol. % of biotite > amphibole > oxides > clinopyroxene, and a few subhedral zircon and apatite crystals (Figure 3c-3d). Modal estimation indicates a monzogranite composition (Le Maitre et al., 2002) (Figure 3e). Plagioclase ranges in composition from An14 to An30, lying within the oligoclase-andesine field, whereas K-feldspars range between Or59 and Or66, lying within the orthoclase-microcline field (Figure 4a, Table 2, Table S1 of the supplementary material). Plagioclase crystals are twinned, showing concentric zoning and sieve textures suggesting a disequilibrium process, where the rim of plagioclase crystallized around the corroded core during a chemical re-equilibrium (cf., Smith, 1974).

On the basis of 23 oxygens, anhydrous cations, the stoichiometric, and the ferric iron content were estimated considering 13eCNK limits, resulting that amphiboles are compositionally magnesio-hornblende according to IMA-2004 (Leake et al., 2004) (Figure 4b, Table 2, Table S1). Fe-Biotite crystals show a mean Fe/(Fe+Mg) value of 0.44 and Ti contents of 0.48–0.53 pfu (Table 1, and Table S1).

Table 1. Thermo-barometric data of Cuitzeo granite xenolith

|

Temperature AVG. |

||

|

Ti in zircon [29 zircon analyses] |

||

|

°C |

SD |

Reference |

|

1 648.91 |

38.78 |

Ferry and Watson, 2007 |

|

2 690.03 |

42.35 |

|

|

13 amphibole analyses |

||

|

693.16 |

28.96 |

Holland and Blundy, 1994 |

|

Pressure AVG. |

||

|

13 amphibole analyses |

||

|

kbar |

SD |

Reference |

|

1.46 |

0.36 |

Mutch et al., 2016 |

|

4.4 [km] |

||

|

1.12 |

0.56 |

Anderson et al., 2008 |

|

log ƒO2 |

SD |

Reference |

|

-12.76 |

0.35 |

Fegley, 2013 |

|

1 aSi=1; aTi=1; 2 aSi=1; aTi=0.6 |

||

Figure 3. Petrographic and mineralogical characteristics of the Cuitzeo xenolith. a) Xenolith within the ignimbrite matrix with lithics. b) Same sample as in (a) cut and polished where the main mineralogy is best observed: subhedral, white plagioclase, anhedral, gray quartz, subhedral K-feldspars in pink tones. Mafic minerals such as biotite and sparingly amphibole are also observed. c) Thin section photomicrograph under cross-polarised light with plagioclase crystals showing twins, concentric zoning, and sieve textures. d) SEM image of main mafic minerals: biotite, amphibole, and oxides around biotite crystals. e) QPF modal classification diagram of xenolith. plg = plagioclase; KF = K feldspar; qz = quartz; ox = oxides; bio = biotite; amph = amphibole.

Geochemistry

Major and Trace Elements

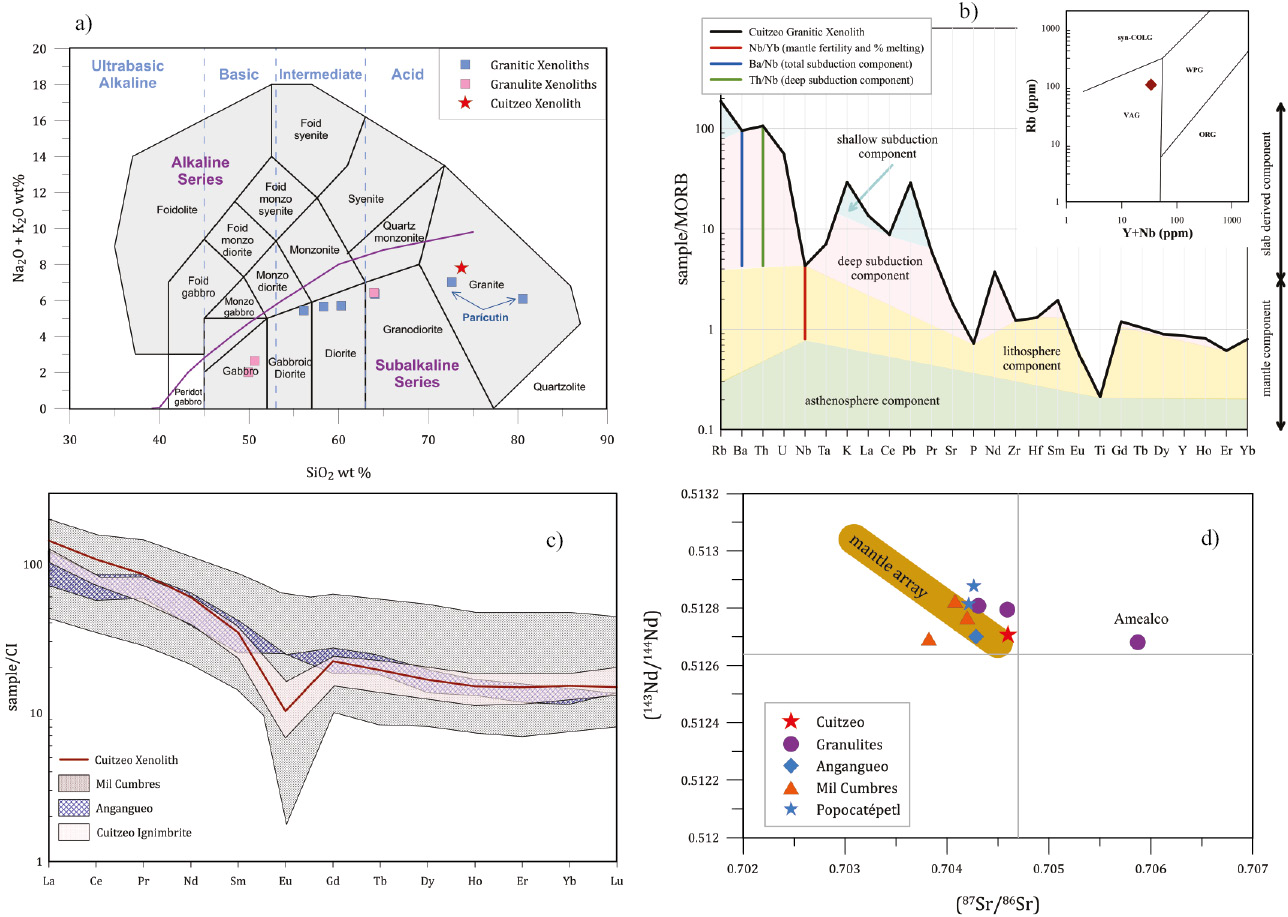

Major elements, trace elements and Sr-Nd isotopes of the studied granitic xenolith of the Czi are consistent with other granitic and granulitic xenoliths reported in the TMVB (Figure 5, and Table 3) (McBirney et al., 1987; Martin del Pozzo, 1990; Aguirre-Díaz et al., 2002; Schaaf et al., 2005; Corona-Chávez et al., 2006; Meriggi et al., 2008; Ortega-Gutiérrez et al., 2014), as well as in the SMC-MALSA volcani<c sequences (Verma and Hasenaka, 2004; Gómez-Vasconcelos et al., 2015; Hernández-Bernal et al., 2016). The granite xenolith contains 73.71 wt.% of SiO2 and shows Mg# = 33 and A/CNK (Al2O3/(CaO+Na2O+K2O)) = 0.99, falling within the metaluminous field. The total alkalis versus silica diagram (Middlemost, 1994) indicates a sub-alkaline trend, which is also similar to the granitic xenoliths reported for the TMVB and granulites of the Valle de Santiago volcanic field and Amealco Caldera (Figure< 1 and 5a). In addition, the sample falls into the granite field, similar to xenoliths found within products of the Paricutín Volcano, which is the youngest of the MGVF (Foshag and González, 1956), whereas other granitic xenoliths of the TMVB are gabbrodiorite-diorite in composition. In comparison, the granulites of the Valle de Santiago volcanic field show mafic compositions whereas the xenolith from Amealco caldera shows felsic compositions. The MORB normalized trace element spider diagram (Figure 5b) is consistent with a subduction setting, as demonstrated by the selective enrichment in the nonconservative (subduction-mobile) elements Rb, Ba, K, Pb, Th and U. By using certain proxies, the pattern can be broken down into four components (Pearce and Peate, 1995; Pearce et al., 2005; Pearce and Stern, 2006). A mantle component with a pattern that passes through the conservative (subduction-immobile) elements (Nb, Ta, Zr, Hf, Ti, HREE) defines the baseline whereas the Nb-Th-Ba component is lithospheric. A component containing all subduction-mobile elements (Rb, Ba, Sr, K, Th, U, LREE, MREE, P, Pb) defines the supercritical fluid or melt released at high temperatures (i.e., usually deep) from subducted crust and sediment. A component containing only the fluid mobile elements (Rb, Ba, K, Sr, Pb) depict the aqueous fluid released at low temperatures (i.e., usually shallow) from the subducted crust or sediments. Also, trace element ratios Yb+Nb versus Rb (inset 5b) suggest a volcanic arc granite affinity (Pearce et al., 1984).

Lastly, the REE chondrite normalized plot (Figure 5c) of the studied granite xenolith, together with the Mil Cumbres, the Cuitzeo ignimbrite and the Angangueo volcanic sequences consistently show a relatively LREE enrichment and a negative Eu anomaly, commonly related to the fractionation of plagioclase (Taylor and McLennan, 2008).

Figure 4. Mineral chemistry of feldspars and amphiboles. a) Plagioclases are oligoclase-andesine, whereas K-feldspar are orthoclase-microcline in composition. b) Most of analyzed crystals are magnesio-hornblende. Data in Table 1, and S1 of the Supplementary material.

Table 2. Representative mineral chemistry of Cuitzeo granite xenolith.

|

Oxide wt % |

Feldspars |

Amphiboles |

|

Biotites |

Fe-Ti oxides |

||||||

|

SiO2 |

65.65 |

60.65 |

62.03 |

48.81 |

50.60 |

36.99 |

0.10 |

||||

|

TiO2 |

---- |

---- |

---- |

0.92 |

0.82 |

4.58 |

2.21 |

||||

|

Al2O3 |

18.53 |

24.07 |

23.17 |

4.76 |

4.08 |

13.21 |

0.93 |

||||

|

FeO Tot |

0.30 |

0.31 |

0.36 |

14.29 |

14.70 |

19.13 |

86.32 |

||||

|

MnO |

---- |

---- |

---- |

0.35 |

0.37 |

0.24 |

0.11 |

||||

|

MgO |

---- |

---- |

---- |

14.67 |

14.96 |

13.02 |

1.27 |

||||

|

CaO |

0.21 |

6.06 |

4.60 |

11.52 |

11.26 |

0.02 |

0.10 |

||||

|

Na2O |

3.81 |

7.61 |

7.91 |

1.51 |

1.43 |

0.47 |

---- |

||||

|

K2O |

10.74 |

0.58 |

0.85 |

0.62 |

0.49 |

9.09 |

---- |

||||

|

TOTAL |

99.23 |

99.28 |

98.91 |

97.46 |

98.72 |

96.10 |

91.04 |

||||

|

cations |

31 oxygens |

23 oxygens |

22 oxygens |

6 oxygens |

|||||||

|

Si |

12.00 |

10.88 |

11.12 |

7.11 |

7.25 |

5.57 |

0.01 |

||||

|

Al IV |

---- |

---- |

---- |

0.82 |

0.69 |

---- |

---- |

||||

|

Al VI |

---- |

---- |

---- |

0.00 |

0.00 |

---- |

---- |

||||

|

Al Tot |

3.99 |

5.09 |

4.90 |

---- |

---- |

2.34 |

0.08 |

||||

|

Ti |

---- |

---- |

---- |

0.10 |

0.09 |

0.52 |

0.13 |

||||

|

Cr |

---- |

---- |

---- |

0.00 |

0.00 |

---- |

---- |

||||

|

Fe 3+ |

---- |

---- |

---- |

0.62 |

0.73 |

---- |

3.78 |

||||

|

Fe 2+ |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

1.15 |

1.05 |

2.41 |

-0.04 |

||||

|

Mn |

---- |

---- |

---- |

0.04 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

||||

|

Mg |

---- |

---- |

---- |

3.19 |

3.20 |

2.92 |

0.14 |

||||

|

Ca |

0.04 |

1.16 |

0.88 |

1.80 |

1.73 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

||||

|

Na |

1.35 |

2.65 |

2.75 |

0.43 |

0.40 |

0.14 |

---- |

||||

|

K |

2.50 |

0.13 |

0.19 |

0.12 |

0.09 |

1.75 |

---- |

||||

|

TOTAL |

19.93 |

19.96 |

19.90 |

15.36 |

15.27 |

15.68 |

4.12 |

||||

|

Name |

An 1.05 |

An 29.54 |

An 23.09 |

Mg-hornblende |

XMag 0.55 |

Ilm 3.25 |

|||||

|

#Mg 74 |

#Mg 75 |

||||||||||

Sr and Nd isotopic ratios

The resulting 86Sr/86Sr and 143Nd/144Nd isotopic values of the studied xenolith are 0.704601 and 0.512706 (εNd = +1.33) respectively, and are shown in Table 3 and Figure 5d. Sr and Nd isotopic signatures from granulites, granitic xenoliths and Early Miocene volcanic follow the mantle array and volcanic arcs. The studied granite xenolith yields a Sm-Nd TDM of 677 Ma, similar to the values reported in granulitic xenoliths of the Valle de Santiago (582 and 900 Ma) (Ortega-Gutiérrez et al., 2014) and Amealco case (683 Ma) (Aguirre-Díaz et al., 2002). The Amealco granulite shows higher Sr radiogenic values than the above-mentioned cases, providing island arcs and active continental signatures (Aguirre-Díaz et al., 2002). However, this Amealco xenolith was transported within a 4.7 Ma eruption. For comparison, granitic xenoliths released at active volcanoes within the TMVB, such as the Popocatépetl volcano, have lower Sr and higher Nd radiogenic values than those of the studied Cuitzeo sample, lying near to the mantle array line. Unfortunately, isotopic data on granitic xenoliths are still scarce for a fully comprehensive comparison.

Figure 5. Geochemical characteristics of the Cuitzeo xenolith and its comparison with other granitic and granulitic xenoliths, volcanic from Early Miocene in Central Mexico (Table 2). a) Classification based on silica and alkali content; all samples lie in the sub-alkaline field. b) MORB normalized trace elements showing proxies as described by (Pearce et al., 1984, 2005; Pearce and Stern, 2006); a typical behavior of magmatic arc rocks is observed. c) Normalized Rare Earth Elements; all data sharing a similar pattern that includes the anomaly of Eu. d) Isotopic (non-initial) relations of Sr and Nd of granitic and granulitic xenoliths of the TMVB; only Amealco granulite shows high values of radiogenic Sr. Also, Miocene volcanic of SMS and MALSA are shown. Dates from Martin del Pozzo (1990), Aguirre-Díaz et al. (2002), Verma and Hasenaka (2004), Schaaf et al. (2005), Meriggi et al. (2008), Ortega-Gutiérrez et al. (2014), Gómez-Vasconcelos et al. (2015), Hernández-Bernal et al.(2016), Trujillo-Hernández (2017).

Table 3. Whole rock major and trace elements, and isotopic ratios of Cuitzeo granite xenolith.

|

Major elements (wt%) |

Trace elements ICP-MS (ppm) |

||||||

|

XRF |

|||||||

|

SiO2 |

73.71 |

Li |

12.59 |

Ba |

600.46 |

||

|

TiO2 |

0.27 |

Be |

2.23 |

La |

34.03 |

||

|

Al2O3 |

13.62 |

P |

0.05 |

Ce |

65.83 |

||

|

Fe2O3 |

2.06 |

Sc |

4.16 |

Pr |

7.91 |

||

|

MnO |

0.02 |

Ti |

0.30 |

Nd |

27.26 |

||

|

MgO |

0.51 |

V |

24.46 |

Sm |

5.11 |

||

|

CaO |

1.67 |

Cr |

6.75 |

Eu |

0.58 |

||

|

Na2O |

4.00 |

Co |

2.96 |

Tb |

0.70 |

||

|

K2O |

3.81 |

Ni |

2.67 |

Gd |

4.40 |

||

|

P2O5 |

0.05 |

Cu |

4.62 |

Dy |

4.09 |

||

|

LOI |

0.17 |

Zn |

20.93 |

Ho |

0.82 |

||

|

Total |

99.88 |

Ga |

17.35 |

Er |

2.36 |

||

|

Rb |

104.72 |

Yb |

2.43 |

||||

|

Isotopic compositions |

Sr |

161.22 |

Lu |

0.36 |

|||

|

87Rb/86Sr |

1.048 |

Y |

24.10 |

Hf |

2.68 |

||

|

87Sr/86Sr |

0.704601 |

Zr |

90.46 |

Ta |

0.92 |

||

|

1σ |

31 |

Nb |

9.99 |

W |

0.31 |

||

|

147Sm/144Nd |

0.126 |

Mo |

1.37 |

Tl |

0.46 |

||

|

143Nd/144Nd |

0.512706 |

Sn |

1.64 |

Pb |

8.67 |

||

|

1σ |

17 |

Sb |

0.26 |

Th |

12.73 |

||

|

TDM (Ma) |

677 |

Cs |

2.55 |

U |

2.62 |

||

U-Pb dating

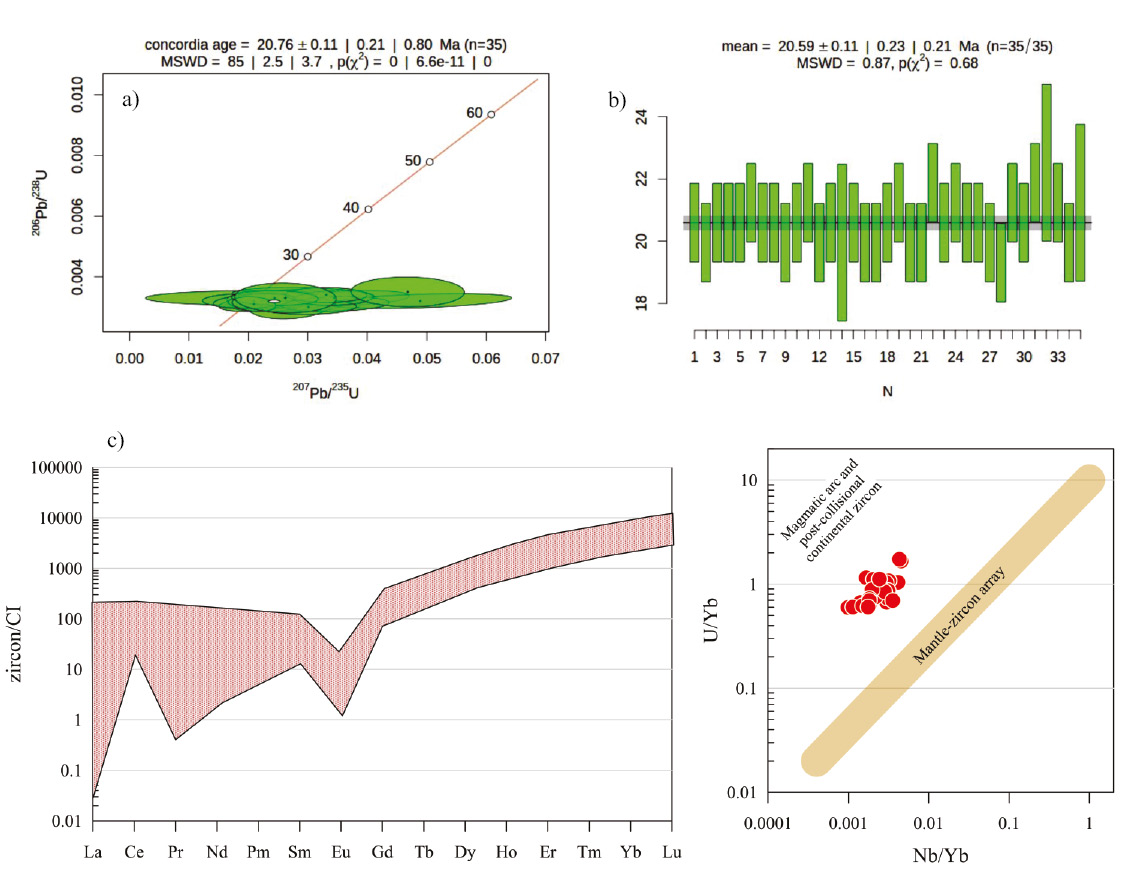

U-Pb geochronological data were obtained from 35 zircons concentrated from the Cuitzeo granitic xenolith (Table 4). Zircons are colorless to slightly pink and range in size from 80 up to 476 µm,showing long and short prismatic morphologies. These crystals provided U-Pb crystallization ages between 19.6 ± 0.8 Ma and 22.4 ± 1.0 Ma, showing the most pronounced peak at 20.6 ± 0.11 Ma (Early Miocene) (Figures 6a and 6b).

The Th/U ratios range between 0.35 and 1.18 with a mean value of 0.53 (Table 4), suggesting an homogenous igneous origin (cf., Hoskin, 2003). The zircon REE pattern shows a positive Ce anomaly, a negative Eu anomaly, as well as a fractionated HREE pattern (Lu/Gd)N varying from 19.4 to 51.6 (Figure 6c). Figure 6d plots along a “mantle-zircon array” reference line. Moreover, the Nb, Yb and U contents in the analyzed zircons lie above the reference line in the “magmatic arc and post-collisional continental” field (Grimes et al., 2015).

Geothermobarometry

Amphibole-plagioclase thermometry values obtained in the studied xenolith range between 655 °C and 737 °C (Holland and Blundy, 1994) (Average= 693.16 °C and STD=28.96). Pressure varies between 1.26 and 1.96 kbar (Average =1.46 kbar and STD=0.36). The Ti-in-zircon thermometer of Ferry and Watson (2007) was also applied to zircons, where Ti contents range from 1.0 to 12.1 ppm (Table S2). Therefore, calculated average temperatures for zircons range from 633 to 862 (aTi=1) °C to 569–764 (aTi=0.6) °C. The calculated average of the highest temperatures is 690.03 °C (STD= 42.35), which tends to be slightly higher than the average obtained from the plagioclase-amphibole thermometer. However, considering the uncertainty of both thermometers, the results are comparable and consistent. Estimation of the oxygen fugacity (ƒO2) and QFM buffer for amphibole compositions was based on the recent P-T calibrations (e.g. Ridolfi and Renzulli (2012), Putirka (2016)) and equations from Fegley (2013), giving log ƒO2 = -12.76 (SD= 0.35).

Table 4. Isotopic data of U-Pb in zircons of Cuitzeo granite xenolith.

|

CORRECTED RATIOS2 |

CORRECTED AGES (Ma) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cuitzeo Xenolith |

U (ppm)1 |

Th (ppm)1 |

Th/U |

207Pb/206Pb |

±2σ abs |

207Pb/235U |

±2σ abs |

206Pb/238U |

±2σ abs |

208Pb/232Th |

±2σ abs |

Rho |

206Pb/238U |

±2σ |

207Pb/235U |

±2σ |

207Pb/206Pb |

±2σ |

Best age (Ma) |

±2σ |

Disc % |

|

|

Zircon_01 |

579 |

202 |

0.35 |

0.0567 |

0.0050 |

0.0245 |

0.0021 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0014 |

0.0001 |

0.14 |

20.5 |

0.6 |

24.6 |

2.1 |

524.0 |

97.0 |

20.5 |

0.6 |

16.5 |

|

|

Zircon_02 |

309.2 |

115.3 |

0.37 |

0.0756 |

0.0094 |

0.0303 |

0.0035 |

0.0031 |

0.0001 |

0.0013 |

0.0001 |

-0.15 |

19.6 |

0.8 |

30.2 |

3.4 |

1070.0 |

130.0 |

19.6 |

0.8 |

35.1 |

|

|

Zircon_03 |

375 |

153.5 |

0.41 |

0.0572 |

0.0065 |

0.0258 |

0.0024 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

-0.14 |

20.3 |

0.8 |

25.9 |

2.4 |

740.0 |

130.0 |

20.3 |

0.8 |

21.7 |

|

|

Zircon_04 |

516 |

304.9 |

0.59 |

0.0625 |

0.0078 |

0.0274 |

0.0029 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

-0.02 |

20.8 |

0.9 |

27.4 |

2.9 |

760.0 |

170.0 |

20.8 |

0.9 |

24.2 |

|

|

Zircon_05 |

434 |

154.8 |

0.36 |

0.0575 |

0.0069 |

0.0248 |

0.0027 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0011 |

0.0001 |

-0.02 |

20.4 |

0.7 |

24.9 |

2.7 |

690.0 |

120 |

20.4 |

0.7 |

18.1 |

|

|

Zircon_06 |

2473 |

1523 |

0.62 |

0.0474 |

0.0027 |

0.0208 |

0.0011 |

0.0033 |

0.0001 |

0.0010 |

0.0000 |

-0.14 |

21.1 |

0.4 |

20.9 |

1.1 |

216.0 |

50.0 |

21.1 |

0.4 |

-0.8 |

|

|

Zircon_07 |

402 |

200.5 |

0.50 |

0.0586 |

0.0071 |

0.0238 |

0.0026 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0011 |

0.0001 |

-0.01 |

20.4 |

0.7 |

23.8 |

2.6 |

680.0 |

100.0 |

20.4 |

0.7 |

14.2 |

|

|

Zircon_08 |

324 |

121.5 |

0.38 |

0.0583 |

0.0068 |

0.0246 |

0.0030 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

-0.09 |

20.6 |

0.8 |

24.6 |

2.9 |

820.0 |

160.0 |

20.6 |

0.8 |

16.4 |

|

|

Zircon_09 |

460.1 |

224.4 |

0.49 |

0.0704 |

0.0067 |

0.0287 |

0.0030 |

0.0031 |

0.0001 |

0.0013 |

0.0001 |

0.03 |

20.2 |

0.9 |

28.7 |

3.0 |

1020.0 |

120.0 |

20.2 |

0.9 |

29.8 |

|

|

Zircon_10 |

344.7 |

175.4 |

0.51 |

0.0656 |

0.0086 |

0.0268 |

0.0032 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0013 |

0.0001 |

0.03 |

20.3 |

0.7 |

26.8 |

3.2 |

870.0 |

150.0 |

20.3 |

0.7 |

24.1 |

|

|

Zircon_11 |

1020 |

560 |

0.55 |

0.0489 |

0.0150 |

0.0220 |

0.0079 |

0.0033 |

0.0001 |

0.0010 |

0.0004 |

0.02 |

20.9 |

0.9 |

22.1 |

8.0 |

400.0 |

270.0 |

20.9 |

0.9 |

5.2 |

|

|

Zircon_12 |

454 |

228 |

0.50 |

0.0511 |

0.0054 |

0.0211 |

0.0019 |

0.0031 |

0.0001 |

0.0010 |

0.0001 |

-0.05 |

20.0 |

0.6 |

21.1 |

2.0 |

418.0 |

89.0 |

20.0 |

0.6 |

5.1 |

|

|

Zircon_13 |

324 |

195 |

0.60 |

0.0429 |

0.0077 |

0.0203 |

0.0033 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0011 |

0.0001 |

-0.04 |

20.8 |

0.8 |

20.4 |

3.2 |

460.0 |

150.0 |

20.8 |

0.8 |

-2.0 |

|

|

Zircon_14 |

346.1 |

152.7 |

0.44 |

0.0617 |

0.0074 |

0.0271 |

0.0030 |

0.0031 |

0.0002 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

0.17 |

20.2 |

1.0 |

27.1 |

3.0 |

755.0 |

90.0 |

20.2 |

1.0 |

25.5 |

|

|

Zircon_15 |

461.5 |

184.9 |

0.40 |

0.0515 |

0.0048 |

0.0217 |

0.0021 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

0.24 |

20.5 |

0.6 |

21.8 |

2.1 |

466.0 |

86.0 |

20.5 |

0.6 |

6.0 |

|

|

Zircon_16 |

393.3 |

176 |

0.45 |

0.0614 |

0.0066 |

0.0259 |

0.0027 |

0.0031 |

0.0001 |

0.0013 |

0.0001 |

0.13 |

19.8 |

0.8 |

25.9 |

2.6 |

880.0 |

130.0 |

19.8 |

0.8 |

23.5 |

|

|

Zircon_17 |

437 |

184.2 |

0.42 |

0.0557 |

0.0059 |

0.0237 |

0.0023 |

0.0031 |

0.0001 |

0.0011 |

0.0001 |

0.15 |

20.1 |

0.7 |

23.8 |

2.3 |

610.0 |

96.0 |

20.1 |

0.7 |

15.5 |

|

|

Zircon_18 |

417 |

192.3 |

0.46 |

0.0550 |

0.0066 |

0.0250 |

0.0029 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

0.14 |

20.9 |

0.6 |

25.0 |

2.9 |

710.0 |

110.0 |

20.9 |

0.6 |

16.4 |

|

|

Zircon_19 |

342.7 |

132 |

0.39 |

0.0842 |

0.0081 |

0.0375 |

0.0039 |

0.0033 |

0.0001 |

0.0019 |

0.0002 |

0.28 |

21.2 |

0.9 |

37.3 |

3.8 |

1320.0 |

110.0 |

21.2 |

0.9 |

43.1 |

|

|

Zircon_20 |

1383 |

1627 |

1.18 |

0.0494 |

0.0033 |

0.0210 |

0.0013 |

0.0031 |

0.0001 |

0.0010 |

0.0000 |

-0.06 |

20.1 |

0.4 |

21.1 |

1.3 |

236.0 |

92.0 |

20.1 |

0.4 |

4.8 |

|

|

Zircon_21 |

549 |

330.9 |

0.60 |

0.0511 |

0.0064 |

0.0216 |

0.0027 |

0.0031 |

0.0001 |

0.0011 |

0.0001 |

0.32 |

20.0 |

0.6 |

21.6 |

2.7 |

363.0 |

140.0 |

20.0 |

0.6 |

7.6 |

|

|

Zircon_22 |

285 |

110.1 |

0.39 |

0.0631 |

0.0110 |

0.0292 |

0.0049 |

0.0034 |

0.0001 |

0.0017 |

0.0002 |

-0.19 |

21.6 |

0.9 |

29.1 |

4.8 |

760.0 |

150.0 |

21.6 |

0.9 |

25.8 |

|

|

Zircon_23 |

334 |

178.9 |

0.54 |

0.1127 |

0.0110 |

0.0489 |

0.0063 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0018 |

0.0003 |

0.41 |

20.7 |

0.7 |

48.3 |

6.0 |

1885.0 |

120.0 |

20.7 |

0.7 |

57.1 |

|

|

Zircon_24 |

391.5 |

202.6 |

0.52 |

0.0541 |

0.0070 |

0.0239 |

0.0031 |

0.0033 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

0.19 |

21.4 |

0.8 |

23.9 |

3.0 |

460.0 |

140.0 |

21.4 |

0.8 |

10.6 |

|

|

Zircon_25 |

472 |

244 |

0.52 |

0.0541 |

0.0053 |

0.0232 |

0.0024 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

-0.02 |

20.7 |

0.6 |

23.2 |

2.4 |

470.0 |

120.0 |

20.7 |

0.6 |

10.7 |

|

|

Zircon_26 |

385 |

210.2 |

0.55 |

0.0518 |

0.0057 |

0.0222 |

0.0023 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0011 |

0.0001 |

0.15 |

20.7 |

0.7 |

22.3 |

2.3 |

475.0 |

79.0 |

20.7 |

0.7 |

7.1 |

|

|

Zircon_27 |

601 |

513 |

0.85 |

0.0824 |

0.0075 |

0.0346 |

0.0037 |

0.0031 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0002 |

0.19 |

20.1 |

0.8 |

34.5 |

3.6 |

1240.0 |

130.0 |

20.1 |

0.8 |

41.7 |

|

|

Zircon_28 |

311 |

134.4 |

0.43 |

0.0687 |

0.0078 |

0.0301 |

0.0033 |

0.0030 |

0.0001 |

0.0014 |

0.0001 |

0.08 |

19.6 |

0.8 |

30.0 |

3.3 |

961.0 |

120.0 |

19.6 |

0.8 |

34.7 |

|

|

Zircon_29 |

517 |

408 |

0.79 |

0.0766 |

0.0065 |

0.0344 |

0.0027 |

0.0033 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

0.12 |

21.0 |

0.6 |

34.3 |

2.6 |

1147.0 |

64.0 |

21.0 |

0.6 |

38.9 |

|

|

Zircon_30 |

400 |

217.2 |

0.54 |

0.0478 |

0.0051 |

0.0209 |

0.0028 |

0.0032 |

0.0001 |

0.0011 |

0.0001 |

0.34 |

20.4 |

0.9 |

21.0 |

2.8 |

390.0 |

130.0 |

20.4 |

0.9 |

2.8 |

|

|

Zircon_31 |

340 |

151.9 |

0.45 |

0.0732 |

0.0074 |

0.0331 |

0.0028 |

0.0034 |

0.0001 |

0.0014 |

0.0001 |

-0.02 |

21.8 |

0.9 |

33.0 |

2.8 |

1090.0 |

110.0 |

21.8 |

0.9 |

33.9 |

|

|

Zircon_32 |

349 |

156 |

0.45 |

0.0997 |

0.0100 |

0.0468 |

0.0039 |

0.0035 |

0.0002 |

0.0022 |

0.0002 |

-0.03 |

22.4 |

1.0 |

47.4 |

3.7 |

1600.0 |

120.0 |

22.4 |

1.0 |

52.7 |

|

|

Zircon_33 |

405 |

214 |

0.53 |

0.0525 |

0.0077 |

0.0244 |

0.0030 |

0.0033 |

0.0001 |

0.0012 |

0.0001 |

-0.12 |

21.5 |

0.8 |

24.5 |

3.0 |

580.0 |

160.0 |

21.5 |

0.8 |

12.4 |

|

|

Zircon_34 |

1232 |

1085 |

0.88 |

0.0485 |

0.0039 |

0.0209 |

0.0015 |

0.0031 |

0.0001 |

0.0010 |

0.0001 |

-0.22 |

19.9 |

0.4 |

21.0 |

1.5 |

297.0 |

87.0 |

19.9 |

0.4 |

5.1 |

|

|

Zircon_35 |

291.4 |

118.2 |

0.41 |

0.0565 |

0.0082 |

0.0262 |

0.0035 |

0.0033 |

0.0002 |

0.0014 |

0.0001 |

-0.06 |

|

21.1 |

1.0 |

26.2 |

3.5 |

740.0 |

100.0 |

21.1 |

1.0 |

19.5 |

Note: 207Pb/206Pb ratios, ages, and errors were calculated according to Petrus and Kamber (2012) . Analyzed spot is 34 μm. See text and Solari et al. (2010) for more detail. Data were measured employing a Thermo X-series inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) coupled to a Resonetics, Resolution M050 excimer laser workstation.

1U and Th concentrations were calculated employing an external standard zircon as in Paton et al. (2010) .

22σ uncertainties propagated according to Paton et al. (2010).

Figure 6. Isotopic and chemical signature of 35 zircon crystals obtained in the Cuitzeo xenolith. a) Concordia diagram displaying a 20.76 ± 0.11 concordant age. b) Weighted mean showing a calculated age of 20.59 ± 0.11 Ma. c) Patterns of the REE contents normalized with chondrite (CI) showing a positive Ce anomaly and a negative Eu anomaly. d) Ratios of U, Yb and Nb that highlight their magmatic character. Note the absence of inherited ages in a) and b). Data in Table 3 and Table S1.

DISCUSSION

Geochemical and isotopic signatures and Miocene magmatic plumbing system

The calc-alkaline type, the REE pattern and age of the Cuitzeo ignimbrite (Czi) and the embedded granite xenolith, are closely comparable to other volcanic complexes of SMC (Gómez-Vasconcelos et al., 2015) (Figure 5c). In fact, the Sr and Nd isotopic signatures of all granitic and granulite xenoliths described in central Mexico lie near the mantle array (Figure 5d) and indicate that the role of crustal assimilation for these magmatic rocks might be negligible. Therefore, the relatively good geochemical, isotopic and geochronological correlation between ignimbrites and the studied granite xenolith, suggest that both the plutonic and volcanic felsic systems could represent the erosional remnants of a shallow magma chamber at ~20 Ma. The explosive volcano-tectonic collapse of its roof at ~18 Ma was possibly structurally controlled by a NNW-SSE graben structure, as described elsewhere by Aguirre-Díaz et al.(2008).

On the other hand, it is worth noticing that the Sm-Nd TDM ages of the granite xenolith and granulites of the Valle de Santiago and Amealco, are Neoproterozoic, ranging between ~683 and 582 Ma while the Valle de Santiago granulites record a zircon individual age of ~497 Ma (Aguirre-Díaz et al., 2002; Ortega-Gutiérrez et al., 2014). However. the absence of pre-Phanerozoic zircons in the dated xenolith apparently does not support the existence of old crust in this region. The Sm-Nd TDM ages of granitic rocks of Cuitzeo region could represent averages and mixtures between mantle and crustal components, particularly of rocks belonging to the Guerrero terrane which possibly include some recycled components of Precambrian and Paleozoic rocks (Ortega-Gutiérrez et al., 2014), and represent the basement of this region of the TMVB.

P–T and physical conditions of granitoid magmatic xenoliths

The relationship between 4.4 ± 1.09 km depth, a temperature of ~690 °C and magnetite-hematite oxygen fugacity behavior suggests that the magma crystalizing as the granitic xenolith of Cuitzeo experienced a baric evolution at shallow crustal level. Closely comparable temperatures obtained from homogenous amphibole and zircon, suggest that a short-lived magmatism, unable to assimilate the country rock, and a relatively rapid cooling could have occurred within a single magma batch, during the ascent, emplacement and crystallization processes.

Younger basement in Central Mexico

Approximately 60 km north of the outcrop of the studied location, a charnockitic-granulite xenolith was found by Ortega-Gutiérrez et al.(2014). These authors argued that the granulite was emplaced at a depth lower than 22 km and the zircon crystallization ages are latest Cretaceous (67.1 Ma), apparently without inheritance from Precambrian or Paleozoic crust. These authors attributed the metamorphism in granulite facies to the continued heating of the crust by basaltic magmas underplating the central TMVB and the northern portion of the MGVF. However, the southern and central parts of the MGVF could overlie at least two different upper crustal granitic basements: i) Eocene granites, considering that 60 km and 120 km to the SW of Cuitzeo, granitic xenoliths in Quaternary lavas (Arócutin and Parícutin, respectively) are correlated with Eocene granitic plutons (Wilcox, 1954; McBirney et al., 1987; Corona-Chávez et al., 2006); and ii) Early Miocene granites related to the Early Miocene granitic xenolith of Cuitzeo Lake.

Implications for Oligocene to Miocene magmatic episodes in Central Mexico

The growth of the magmatic arcs, which are the main factories of continental crust on Earth, and in particular those formed onto continental lithosphere, is highly episodic, punctuated by simple or high-volume magmatic pulses termed “flare-ups” (Ducea et al., 2015; Paterson and Ducea, 2015). The geographic distribution of rocks of the two main Cenozoic volcanic belts shows a relative overlap along the Pacific coast and Central México, but the frequency distribution of isotopic ages records peaks at about 30 Ma, 23 Ma, 10 Ma, and 4 Ma. Peaks are considered to reflect the intensity of magmatic activity in a region where volumetric estimations are missing (Ferrari et al., 1999). After a major episode of ignimbritic volcanism in the Sierra Madre Occidental, the so-called ignimbrite flare-up at ~38 and ~25 Ma, a counterclockwise rotation of 30° of the arc occurred. Then, less voluminous silicic volcanism occurred during the Early Miocene (25–17 Ma)(Pasquarè et al., 1991; Cerca-Martínez et al., 2000; Lenhardt et al., 2010; Pérez-Esquivias et al., 2010; Bryan and Ferrari, 2013; Arce et al., 2015). In northern Michoacán, the Early Miocene magmatism represents a voluminous eruptive period, which has been initiated with mainly andesite compositions (SMC and MALSA andesites) and continued with predominantly ignimbritic volcanism (Sierra de Mil Cumbres and Cuitzeo region) at ~18–16 Ma. The ~20.6 Ma granite xenolith found within the Cuitzeo ignimbrite represents the Early Miocene intrusive counterpart of some intermediate or silicic volcanic rocks. Successively, the Early Miocene volcanism continued, as represented by the Copándaro unit (>18.7 Ma) and the Cuitzeo lavas (Czl) (>18.3 Ma), which are older than the Cuitzeo ignimbrite (16.88 ± 0.34 Ma)). The conspicuous presence of such felsic rocks suggests the development of recurrent episodic felsic magmatism in this region. The volume of the Miocene explosive volcanism of the Sierra de Mil Cumbres was large, although perhaps unquantifiable due to the strong tectonic erosion produced by normal faulting (Garduño-Monroy et al., 2009). After a long period of felsic volcanic quiescence over the Early Pleistocene (1.48 Ma), an atypical and explosive event occurred with an unknown source, dispersing the Cuitzeo fallout (Czf), which mantled the 18.69 Ma Cuitzeo lava flows (Czl) and, locally, the 17.42 Ma Cuitzeo ignimbrite unit (Czi). Later on, the MGVF started to develop in the Late Pliocene (Avellán et al., 2020).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The ~16.88 Ma Cuitzeo ignimbrite hosts a calc-alkaline metaluminous granitic xenolith providing a concordant zircon (U-Pb) age of 20.6 ± 0.1 Ma without older or inherited components. Major and trace elements of whole rock and zircon crystals, as well as the isotopic Sr and Nd signatures show magmatic arc signatures near the mantle array line. Thermobarometric constraints of the Cuitzeo granitic xenolith suggest it is a remnant of a felsic ~4 km shallow magma chamber from the Early Miocene plumbing magmatic system. However, to understand the recurrence of calderic felsic systems over the Early to Middle Miocene in central Mexico, further petrological and chronological studies are required.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Table S1. Mineral chemistry of Cuitzeo granite xenolith, and Table S2. Trace elements in dated zircons crystals, can be found in the webpage of this journal: www.rmcg.unam.mx; “in press/draft” section.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The manuscript benefited greatly from the critical comments by Natalia Pardo, Adrián Pittari and Miguel A. Parada. The authors are also thankful to Lozano-SantaCruz and Ofelia Pérez-Arvizu for analytical support in XRF and ICPMS analyses respectively. Isotopic measurements of U-Pb, Sr and Nd were carried out by Carlos Ortega-Obregón, Gabriela Solís-Pichardo, Gerardo Arrieta-García and Teodoro Hernández-Treviño. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Víctor Hugo Garduño-Monroy, pioneer geologist in Michoacán. We thank project PAPIIT-IA106217 for financial support.

REFERENCES

Aguirre-Díaz, G.J., Dubois, M., Laureyns, J., Schaaf, P., 2002, Nature and P-T conditions of the crust beneath the central mexican volcanic belt based on a precambrian crustal xenolith: International Geology Review, 44, 222-242.

Aguirre-Díaz, G.J., Labarthe-Hernández, G., Tristán-González, M., Nieto-Obregón, J., Gutiérrez-Palomares, I., 2008, Chapter 4: The Ignimbrite Flare-Up and Graben Calderas of the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico: Amsterdam, Developments in Volcanology, Elsevier, 10, 143-180.

Anderson, J.L., Barth, A.P., Wooden, J.L., Mazdab, F., 2008, Thermometers and thermobarometers in granitic systems: Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 69, 121-142.

Aranda-Gómez, J.J., Luhr, J.F., 1996, Origin of the Joya Honda maar, San Luis Potosí, México: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 74, 1-18.

Aravena, A., Gutiérrez, F.J., Parada, M.A., Payacán, Bachmann, O., Poblete, F., 2017, Compositional zonation of the shallow La Gloria pluton (Central Chile) by late-stage extraction/redistribution of residual melts by channelization: Numerical modeling: Lithos, 284-285, 578-587.

Arce, J.L., Layer, P., Martínez, I., Salinas, J.I., Macías-Romo, M. del C., Morales-Casique, E., Benowitz, J., Escolero, O., Lenhardt, N., 2015, Geología y estratigrafía del pozo profundo San Lorenzo Tezonco y de sus alrededores, sur de la Cuenca de México: Boletín la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 67, 123-143.

Avellán, D.R., Cisneros-Máximo, G., Macías, J.L., Gómez-Vasconcelos, M.G., Layer, P.W., Sosa-Ceballos, G., Robles-Camacho, J., 2020, Eruptive chronology of monogenetic volcanoes northwestern of Morelia – Insights into volcano-tectonic interactions in the central-eastern Michoacán-Guanajuato Volcanic Field, México: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 100, Article 102554, 1-23.

Bryan, S.E., Ferrari, L., 2013, Large igneous provinces and silicic large igneous provinces: Progress in our understanding over the last 25 years: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, 125, 1053-1078.

Castro-Dorado, A., 2015, Petrografía de rocas ígneas y metamórficas; Madrid, España, Paraninfo, 260 pp.

Cerca-Martínez, L.M., Aguirre-Díaz, G. de J., López-Martínez, M., Martínez, L.M.C., Díaz, G.D.J.A., Martínez, M.L., 2000, The geologic evolution of the southern Sierra de Guanajuato, México: A documented example of the transition from the Sierra Madre Occidental to the Mexican Volcanic Belt: International Geology Review, 42, 131-151.

Condie, K.C., 2016, The Crust, in Earth as an Evolving Planetary System: London, United Kingdom, Academic Press, 9-41.

Cooper, G.F., Blundy, J.D., Macpherson, C.G., Humphreys, M.C.S., Davidson, J.P., 2019, Evidence from plutonic xenoliths for magma differentiation, mixing and storage in a volatile-rich crystal mush beneath St. Eustatius, Lesser Antilles: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 174, Article 39, 1-24.

Corona-Chávez, P., Reyes-Salas, M., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., Israde-Alcántara, I., Lozano-Santa Cruz, R., Morton-Bermea, O., Hernández-Álvarez, E., 2006, Asimilación de xenolitos graníticos en el Campo Volcánico Michoacán-Guanajuato: El caso de Arócutin Michoacán, México: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 23, 233-245.

DePaolo, D.J., 1981, Trace element and isotopic effects of combined wallrock assimilation and fractional crystallization: Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 53, 189-202.

Ducea, M.N., Saleeby, J.B., Bergantz, G., 2015, The Architecture, Chemistry, and Evolution of Continental Magmatic Arcs: Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 43, 299-331.

Edmonds, M., Cashman, K. V., Holness, M., Jackson, M., 2019, Architecture and dynamics of magma reservoirs: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 377, Article 20180298, 1-29.

Ewart, A., Cole, J.W., 1967, Textural and Mineralogical Significance of the Granitic Xenoliths From the Central Volcanic Region, North Island, New Zealand: New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 10, 31-54.

Fegley, B., 2013, Practical Chemical Thermodynamics for Geoscientists, Practical Chemical Thermodynamics for Geoscientists: Massachusetts, United States, Elsevier Inc., 674 pp.

Ferrari, L., López-Martínez, M.M., Aguirre-Díaz, G.J., Carrasco-Núñez, G., 1999, Space-time patterns of Cenozoic arc volcanism in central Mexico: From the Sierra Madre Occidental to the Mexican Volcanic Belt: Geology 27, 303-306.

Ferrari, L., Pasquarè, G., Venegas-Salgado, S., Romero-Rios, F., 2000, Geology of the western Mexican Volcanic Belt and adjacent Sierra Madre Occidental and Jalisco block: Special Paper of the Geological Society of America, 334, 65-83.

Ferrari, L., Orozco-Esquivel, T., Manea, V., Manea, M., 2012, The dynamic history of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and the Mexico subduction zone: Tectonophysics 522-523, 122-149.

Ferry, J.M., Watson, E.B., 2007, New thermodynamic models and revised calibrations for the Ti-in-zircon and Zr-in-rutile thermometers: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 154, 429-437.

Foshag, W.F., Gonzalez, R.J., 1956, Birth and development of Paricutin Volcano, Mexico: United States Geological Survey Bulletin, 965-D, 355-489.

Garduño-Monroy, V.H., Pérez-Lopez, R., Israde-Alcantara, I., Rodríguez-Pascua, M.A., Szynkaruk, E., Hernández-Madrigal, V.M., García-Zepeda, M.L., Corona-Chávez, P., Ostroumov, M., Medina-Vega, V.H., García-Estrada, G., Carranza, O., Lopez-Granados, E., Mora Chaparro, J.C., 2009, Paleoseismology of the southwestern Morelia-Acambay fault system, central Mexico: Geofísica Internacional, 48, 319-335.

Gómez-Vasconcelos, M.G., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., Macías, J.L., Layer, P.W., Benowitz, J.A., 2015, The Sierra de Mil Cumbres, Michoacán, México: Transitional volcanism between the Sierra Madre Occidental and the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 301, 128-147.

Gómez-Vasconcelos, M.G., Luis Macías, J., Avellán, D.R., Sosa-Ceballos, G., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., Cisneros-Máximo, G., Layer, P.W., Benowitz, J., López-Loera, H., López, F.M., Perton, M., 2020, The control of preexisting faults on the distribution, morphology, and volume of monogenetic volcanism in the Michoacán-Guanajuato Volcanic Field: Geological Society of America Bulletin, 132 (11-12), 2455–2474.

Grimes, C.B., Wooden, J.L., Cheadle, M.J., John, B.E., 2015, “Fingerprinting” tectono-magmatic provenance using trace elements in igneous zircon: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 170, 1-26.

Hasenaka, T., Carmichael, I.S.E., 1985, A compilation of location, size, and geomorphological parameters of volcanoes of the Michoacan-Guanajuato volcanic field, central Mexico: Geofísica Internacional, 24, 577-607.

Hernández-Bernal, M.S., Corona-Chávez, P., Solís-Pichardo, G., Schaaf, P., Solé-Viñas, J., Molina, J.F., 2016, Miocene andesitic lavas of Sierra de Angangueo: A petrological, geochemical, and geochronological approach to arc magmatism in Central Mexico: International Geology Review, 58, 603-625.

Holland, T., Blundy, J., 1994, Non-ideal interactions in calcic amphiboles and their bearing on amphibole-plagioclase thermometry: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 116, 433-447.

Hoskin, P.W.O., 2003. The Composition of Zircon and Igneous and Metamorphic Petrogenesis: Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 53, 27-62.

Israde-Alcántara, I., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., Fisher, C.T., Pollard, H.P., Rodríguez-Pascua, M.A., 2005, Lake level change, climate, and the impact of natural events: The role of seismic and volcanic events in the formation of the Lake Patzcuaro Basin, Michoacan, Mexico: Quaternary International, 135, 35-46.

Le Maitre, R., Streckeisen, A., Zanettin, B., Le Bas, M., Bonin, B., Bateman, P. (eds.), Igneous rocks : a classification and glossary of terms : recommendations of the International Union of Geological Sciences, Subcommission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks: New York, United States, Cambridge University Press, 236 pp.

Leake, B.E., Woolley, A.R., Birch, W.D., Burke, E.A.J., Ferraris, G., Grice, J.D., Hawthorne, F.C., Kisch, H.J., Krivovichev, V.G., Schumacher, J.C., Stephenson, N.C.N., Whittaker, E.J.W., 2004, Nomenclature of amphiboles: Additions and revisions to the International Mineralogical Association’s amphibole nomenclature: American Mineralogist, 89, 883-887.

Lenhardt, N., Böhnel, H., Wemmer, K., Torres-Alvarado, I.S., Hornung, J., Hinderer, M., 2010, Petrology, magnetostratigraphy and geochronology of the Miocene volcaniclastic Tepoztlán Formation: Implications for the initiation of the Transmexican Volcanic Belt (Central Mexico): Bulletin of Volcanology, 72, 817-832.

Martin del Pozzo, A.L., 1990, Geoquímica y paleomagnetismo de la Sierra de Chichinautzin: México, D.F. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ph.D. Thesis, 235 pp.

McBirney, A.R.R., Taylor, H.P.P., Armstrong, R.L.L., 1987, Paricutin re-examined: a classic example of crustal assimilation in calc-alkaline magma: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 95, 4-20.

Meriggi, L., Macías, J.L., Tommasini, S., Capra, L., Conticelli, S., 2008, Heterogeneous magmas of the Quaternary Sierra Chichinautzin volcanic field (central Mexico): The role of an amphibole-bearing mantle and magmatic evolution processes: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 25, 197-216.

Middlemost, E.A.K., 1994, Naming materials in the magma/igneous rock system: Earth Science Reviews, 37(3-4), 215-224.

Mutch, E.J.F., Blundy, J.D., Tattitch, B.C., Cooper, F.J., Brooker, R.A., 2016, An experimental study of amphibole stability in low-pressure granitic magmas and a revised Al-in-hornblende geobarometer: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 171, 85.

Ortega-Gutiérrez, F., Gómez-Tuena, A., Elías-Herrera, M., Solari, L.A., Reyes-Salas, M., Macías-Romo, C., 2014, Petrology and geochemistry of the Valle de Santiago lower-crust xenoliths: Young tectonothermal processes beneath the central Trans-Mexican volcanic belt: Lithosphere, 6, 335-360.

Ortega-Gutiérrez, F., Martiny, B.M., Morán-Zenteno, D.J., Reyes-Salas, A.M., Solé-Viñas, J., 2011, Petrology of very high temperature crustal xenoliths in the Puente Negro intrusion: A sapphire-spinel-bearing Oligocene andesite, Mixteco terrane, southern Mexico: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 28, 593-629.

Pasquarè, G., Ferrari, L., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., Tibaldi, A., Vezzoli, L., 1991, Geology of the central sector of the Mexican Volcanic belt, States of Guanajuato and Michoacán: Geological Society of America Map and Chart series, MCH072, 22 pp.

Paterson, S.R., Ducea, M.N., 2015, Arc Magmatic Tempos: Gathering the Evidence: Elements, 11, 91-98.

Paton C., Woodhead J.D., Hellstrom J.C., Hergt J.M., Greig A., Maas R., 2010, Improved laser ablation U-Pb zircon geochronology through robust downhole fractionation correction: Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems, 11, 1-36.

Pearce, J.A., Peate, D.W., 1995, Tectonic Implications of the Composition of Volcanic arc Magmas: Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 23, 251-285.

Pearce, J.A., Stern, R.J., 2006, Origin of back-arc basin magmas: Trace element and isotope perspectives: Geophysical Monograph Series, 166, 63-86.

Pearce, J.A., Harris, N.B.W., Tindle, A.G., 1984, Trace element discrimination diagrams for the tectonic interpretation of granitic rocks: Journal of Petrology, 25, 956-983.

Pearce, J.A., Stern, R.J., Bloomer, S.H., Fryer, P., 2005, Geochemical mapping of the Mariana arc-basin system: Implications for the nature and distribution of subduction components: Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 6 (7), 1-27.

Pérez-Esquivias, H., Macías-Vázquez, J.L., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., Arce-Saldaña, José Luis García-Tenorio, F., Castro-Govea, R., Layer, P., Saucedo-Girón, R., Martínez, C., Jiménez-Haro, A., Valdés, G., Meriggi, L., Hernández, R., 2010, Estudio vulcanológico y estructural de la secuencia estratigráfica Mil Cumbres y del campo geotérmico de Los Azufres, Mich: Geotermia, 51-63.

Petrus, J.A. Kamber, B.S., 2012, VizualAge: A Novel Approach to Laser Ablation ICP‐MS U‐Pb Geochronology Data Reduction: Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research, 36, 247-270.

Pier, J.G., Podosek, F.A., Luhr, J.F., Brannon, J.C., Louis, S., Aranda-Gomez, J.J., 1989, Spinel-lherzolite-bearing quaternary volcanic centers in San Luis Potosí, Mexico: 2. SR and ND Isotopic Systematics: Journal of Geophysical Research, 94, 7941.

Pittari, A., Cas, R.A.F., Wolff, J.A., Nichols, H.J., Larson, P.B., Martí, J., 2008, Chapter 3 The Use of Lithic Clast Distributions in Pyroclastic Deposits to Understand Pre- and Syn-Caldera Collapse Processes: A Case Study of the Abrigo Ignimbrite, Tenerife, Canary Islands: Developments in Volcanology, 97-142.

Pola, A., Martínez-Martínez, J., Macías, J.L., Fusi, N., Crosta, G., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., Núñez-Hurtado, J.A., 2016, Geomechanical characterization of the Miocene Cuitzeo ignimbrites, Michoacán, Central Mexico: Engineering Geology, 214, 79-93.

Putirka, K., 2016, Amphibole thermometers and barometers for igneous systems and some implications for eruption mechanisms of felsic magmas at arc volcanoes: American Mineralogist, 101, 841-858.

Ridolfi, F., Renzulli, A., 2012, Calcic amphiboles in calc-alkaline and alkaline magmas: Thermobarometric and chemometric empirical equations valid up to 1,130°C and 2.2 GPa: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 163, 877-895.

Rudnick, R.L., Gao, S., 2013, Composition of the Continental Crust, 2nd ed, Treatise on Geochemistry: Second Edition: Oxford, United Kingdom, Elsevier, 3, 1-64.

Rudnick, R.L., Taylor, S.R., 1987, The composition and petrogenesis of the lower crust: A xenolith study: Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 92, 13981-14005.

Schaaf, P., Heinrich, W., Besch, T., 1994, Composition and SmNd isotopic data of the lower crust beneath San Luis Potosí, central Mexico: Evidence from a granulite-facies xenolith suite: Chemical Geology, 118, 63-84.

Schaaf, P., Stimac, J., Siebe, C., Macías, J.L., 2005, Geochemical evidence for mantle origin and crustal processes in volcanic rocks from Popocatépetl and surrounding monogenetic volcanoes, central Mexico: Journal of Petrology, 46, 1243-1282.

Schmincke, H.-U., 2004, Volcanism: Berlin Heidelberg, Springer, 324 pp.

Smith, J.V., 1974, Intergrowths of Feldspars with Other Minerals, in Feldspar Minerals. Berlin Heidelberg, Springer, 553-647.

Sparks, R.S.J., Annen, C., Blundy, J.D., Cashman, K. V., Rust, A.C., Jackson, M.D., 2019, Formation and dynamics of magma reservoirs: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 377, Article 20180019, 1-30.

Solari, L.A., Gómez-Tuena, A., Bernal, J.P., Pérez-Arvizu, O., Tanner, M., 2010, U-Pb zircon geochronology by an integrated LA-ICP-MS microanalytical workstation: achievements in precision and accuracy: Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research, 34 (1), 5-18. Szynkaruk, E., Garduño-Monroy, V.H., Bocco, G., 2004, Active fault systems and tectono-topographic configuration of the central Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt: Geomorphology, 61, 111-126.

Taylor, S.R., McLennan, S., 2008, Planetary Crusts: New York, United States, Cambridge University Press, 378 pp.

Tegner, C., Wilson, J.R., Robins, B., 2005, Crustal assimilation in basalt and jotunite: Constraints from layered intrusions: Lithos, 83, 299-316.

Trujillo-Hernández, N., 2017, Estudio geológico, geoquímico y mineralógico de las secuencias volcánicas de la porción suroeste del Lago de Cuitzeo, Michoacán, ligadas a la zona geotérmica de San Agustín del Maíz: Morelia, México, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás Hidalgo, MSc. Thesis, 110 pp.

Urrutia-Fucugauchi, J., Uribe-Cifuentes, R.M., 1999, Lower-crustal xenoliths from the Valle de Santiago maar field, Michoacán-Guanajuato volcanic field, Central Mexico: International Geology Review, 41, 1067-1081.

Verma, S.P., Hasenaka, T., 2004, Sr, Nd, and Pb isotopic and trace element geochemical constraints for a veined-mantle source of magmas in the Michoacán-Guanajuato volcanic field, west-central Mexican Volcanic Belt: Geochemical Journal, 38, 43-65.

Watts, K.E., John, D.A., Colgan, J.P., Henry, C.D., Bindeman, I.N., Schmitt, A.K., 2016, Probing the volcanic-plutonic connection and the genesis of crystal-rich rhyolite in a deeply dissected supervolcano in the Nevada Great Basin: Source of the late Eocene Caetano Tuff: Journal of Petrology, 57, 1599-1644.

Wilcox, R.E., 1954, Petrology of Paricutin region: United States Geological Survey Bulletin, 965-C, 281-353.

Yavuz, F., Döner, Z., 2017, WinAmptb: A windows program for calcic amphibole thermobarometry: Periodico di Mineralogia, 86, 135-167.