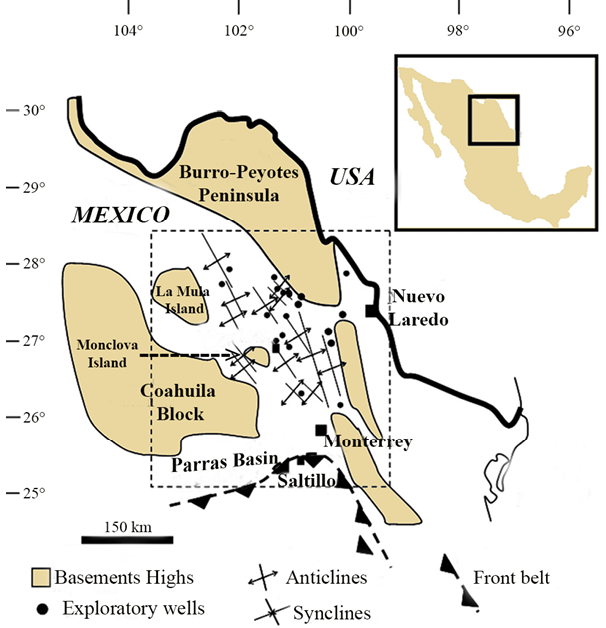

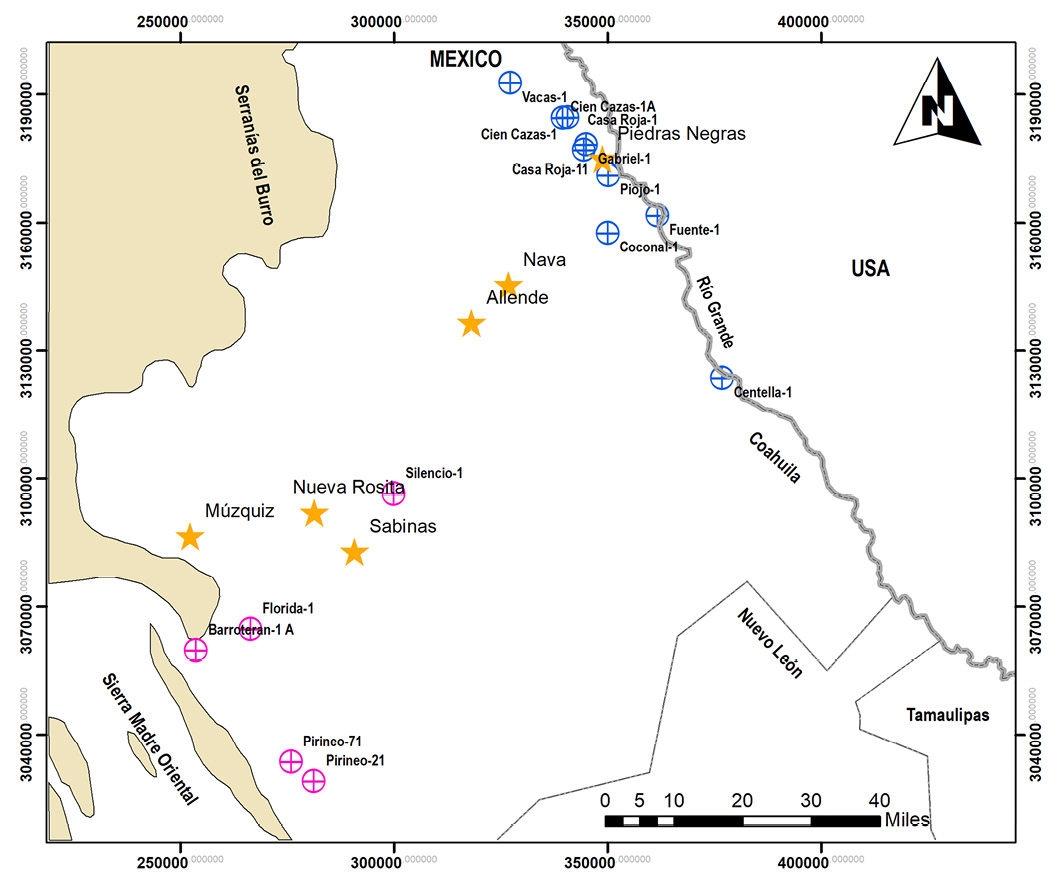

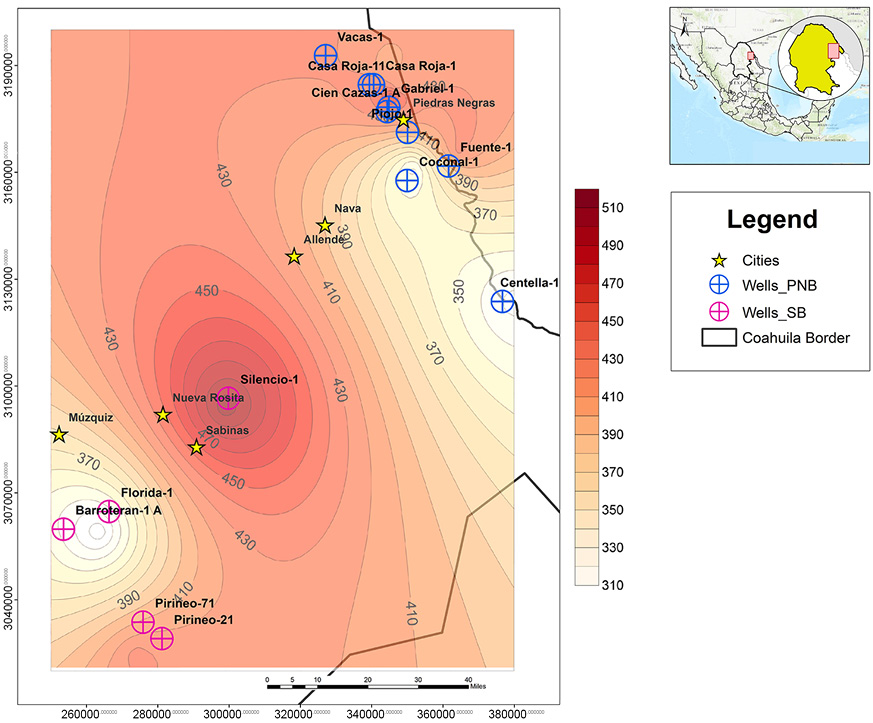

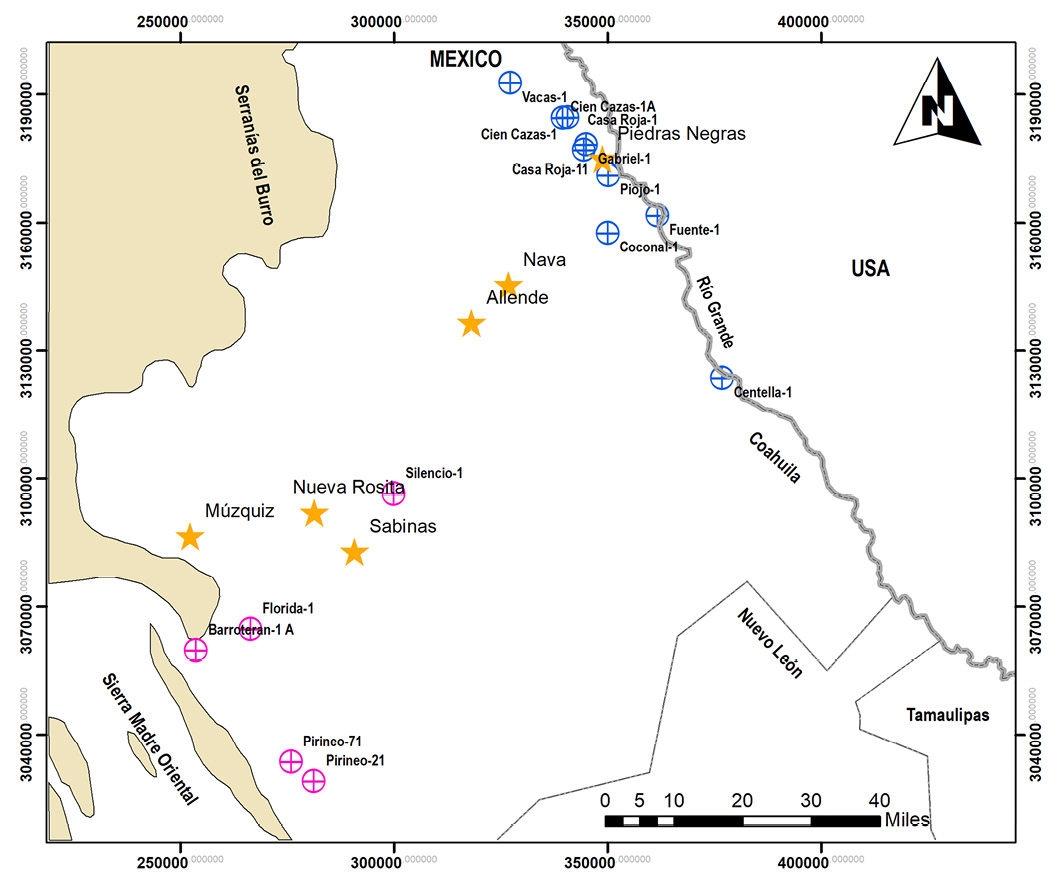

Figure 4. Location of the 15 wells in the SB-PNB, where rock samples were used for the Rock-Eval analysis of the La Peña Formation. Sabinas basin wells: pink color, Piedras Negras basin wells: blue color.

RESULTS

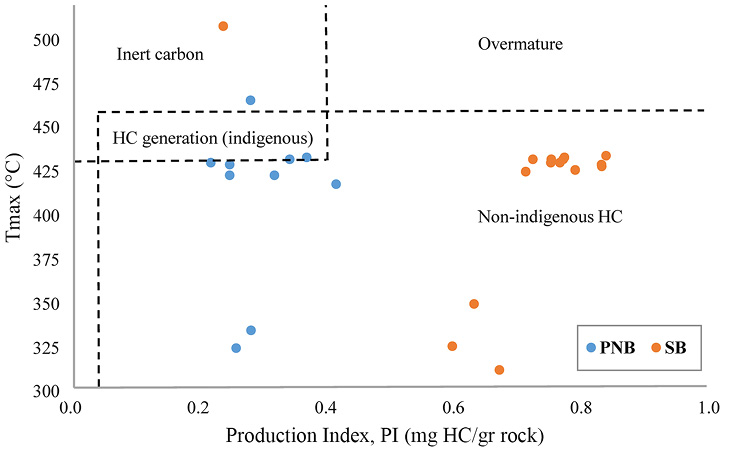

The Rock-Eval S1 peak indicates the amount of detectable free hydrocarbons before thermal pyrolysis present within a sample (Karg and Littke, 2020). The S1 peak values from the studied samples fluctuate from 0.02 to 22.23 mg HC/g rock (avg. 6.48 mg HC/g rock). The present petroleum generation potential, given by the S2 peak varies from 0.06 to 4.79 mg HC/g rock (avg. 1.96 mg HC/g rock). The Production Index (PI), a maturity proxy defined as the ratio of hydrocarbons liberated under the S1 peak to the total amount of hydrocarbons released under S1 and S2 peaks, ranges between 0.22 to 0.84 (avg. 0.55). The main Rock-Eval pyrolysis results are shown in Table 2.

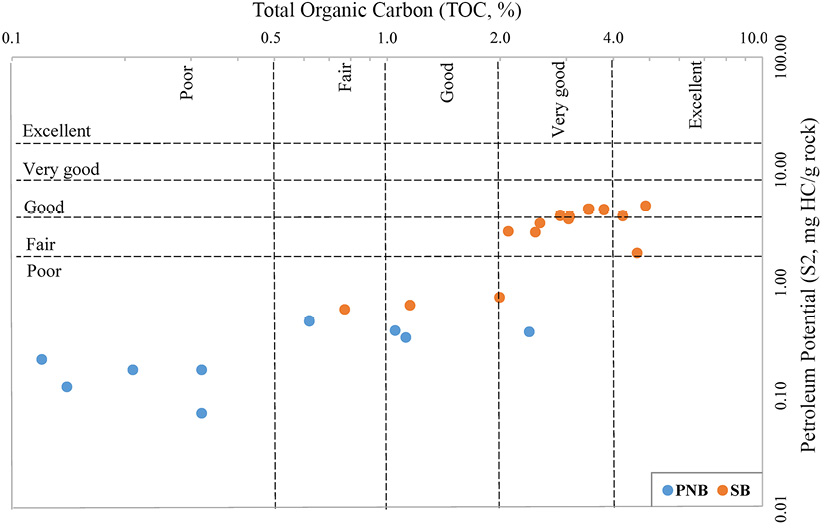

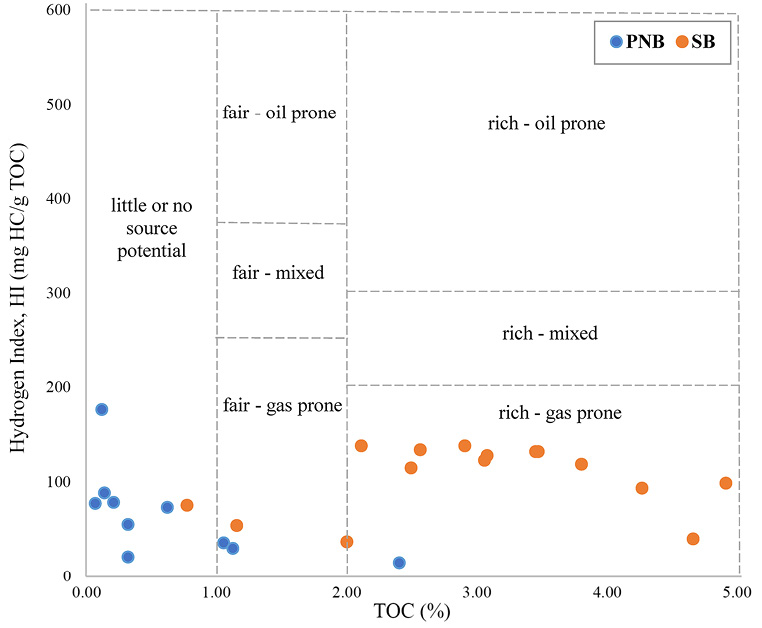

The Total Organic Carbon (TOC) content of a rock represents all the biogenically derived carbon, which consists of two components: hydrocarbons (oil, gas) and solid organic matter known as kerogen (Hart and Steen, 2015). The La Peña Formation TOC content varies from 0.07 to 2.39 % (avg. 0.64 %) and from 0.77 to 4.88 % (avg. 2.96 %) in the Piedras Negras and Sabinas basins, respectively.

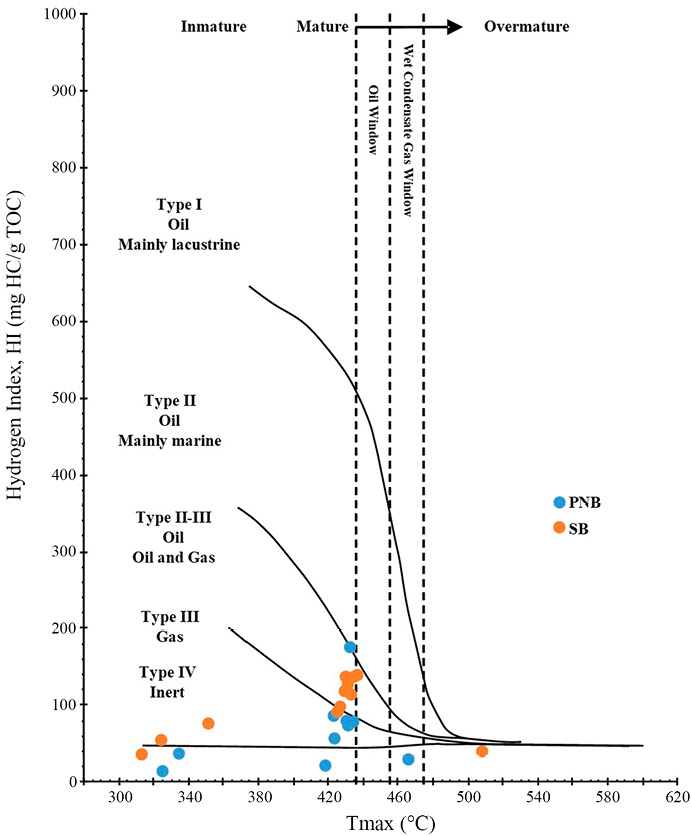

The Hydrogen Index (HI) has values ranging from 15 to 175 mg HC/g TOC (avg. 64.80 mg HC/g TOC) for the Piedras Negras basin and from 37 to 137 mg HC/g TOC (avg. 103.13 mg HC/g TOC) for the Sabinas basin. All the analysed samples can be described as hydrogen-poor organic matter with HI <200 mg HC/g TOC.

The Tmax values range between 325 to 466 °C (avg. 411.40 °C) and between 312 to 508 °C (avg. 415.13 °C) for the Piedras Negras and Sabinas basins, respectively. Overall, nine samples are located close to the oil generation zone and just two presented a thermal maturity enough to the generation of wet and dry gas, the rest showed Tmax values for an immature source rock. The distribution of this thermal maturity parameter indicates that the mature and overmature samples (435 to 508 °C) are in the center of the study area (Sabinas basin; Figure 5).

Figure 5. Iso-value map of the La Peña Formation showing the geographical distribution in the study area for Thermal maturity (Tmax).

Figure 6. Diagram of the La Peña Formation Total Organic Carbon (TOC) vs. Petroleum Generative Potential (S2 peak) according to the Rock-Eval pyrolysis results. SB: Sabinas Basin, PNB: Piedras Negras Basin.

Figure 7. Diagram of the La Peña Formation Hydrogen Index vs. Tmax (°C), showing type of Kerogen and thermal maturity for the analysed samples in the study area.

Figure 8. The La Peña Formation Production Index (PI) vs. Tmax (°C) diagram for the analysed samples in the study area.

Figure 9. The La Peña Formation TOC vs. HI cross plot showing the potential hydrocarbons according to the Rock-Eval pyrolysis data.

Table 2. Rock-Eval pyrolysis data for the 25 rock samples of the La Peña Formation. PNB: Piedras Negras Basin, SB: Sabinas Basin. S3 peak: amount of generated CO2 during thermal pyrolysis The Hydrogen Index (HI) (mg HC/g TOC) and the OI (mg CO2/g TOC) were calculated to distinguish the type of kerogen, derived from the S2 and S3 peaks, respectively, by normalization to the TOC content (Karg and Littke, 2020).

|

Well

|

Basin

|

Depth

|

TOC

|

HI

|

OI

|

Tmax

|

S1

|

S2

|

PI

|

|

|

(m)

|

(%wt)

|

(mg HC/g TOC)

|

(mg CO2/g TOC)

|

(°C)

|

(mg HC/g rock)

|

(S1/S1+S2)

|

|

Coconal-1

|

PNB

|

2267

|

1.05

|

36

|

14

|

335

|

0.15

|

0.38

|

0.28

|

|

Casa Roja-1

|

PNB

|

1984

|

0.32

|

21

|

6

|

418

|

0.05

|

0.07

|

0.42

|

|

Gabriel-1

|

PNB

|

1991

|

0.32

|

55

|

41

|

423

|

0.08

|

0.17

|

0.32

|

|

Casa Roja-11

|

PNB

|

1922

|

0.14

|

88

|

22

|

423

|

0.04

|

0.12

|

0.25

|

|

Vacas-1

|

PNB

|

1747

|

0.12

|

175

|

10

|

432

|

0.11

|

0.21

|

0.34

|

|

Cien Cazas-1 A

|

PNB

|

2022

|

1.12

|

30

|

8

|

466

|

0.13

|

0.33

|

0.28

|

|

Fuente-1

|

PNB

|

2402

|

0.21

|

78

|

0

|

433

|

0.1

|

0.17

|

0.37

|

|

Piojo-1

|

PNB

|

2138

|

0.62

|

73

|

22

|

430

|

0.13

|

0.46

|

0.22

|

|

Cien Cazas-1

|

PNB

|

2055

|

0.07

|

77

|

0

|

429

|

0.02

|

0.06

|

0.25

|

|

Centella-1

|

PNB

|

2571

|

2.39

|

15

|

6

|

325

|

0.13

|

0.37

|

0.26

|

|

Silencio-1

|

SB

|

910

|

4.63

|

40

|

6

|

508

|

0.58

|

1.84

|

0.24

|

|

Barroteran-1 A

|

SB

|

580 – 585

|

0.77

|

75

|

0

|

350

|

1

|

0.58

|

0.63

|

|

Florida-1

|

SB

|

1375 – 1380

|

1.99

|

37

|

5

|

312

|

1.52

|

0.74

|

0.67

|

|

Florida-1

|

SB

|

1410 – 1415

|

1.15

|

54

|

4

|

326

|

0.94

|

0.63

|

0.60

|

|

Pirineo-71

|

SB

|

1315

|

2.1

|

137

|

5

|

434

|

15.03

|

2.87

|

0.84

|

|

Pirineo-71

|

SB

|

1320

|

2.55

|

133

|

15

|

433

|

11.64

|

3.39

|

0.77

|

|

Pirineo-71

|

SB

|

1335

|

2.48

|

114

|

12

|

432

|

7.43

|

2.82

|

0.72

|

|

Pirineo-71

|

SB

|

1350

|

3.45

|

131

|

30

|

432

|

15.29

|

4.5

|

0.77

|

|

Pirineo-71

|

SB

|

1355

|

3.43

|

131

|

12

|

432

|

13.74

|

4.49

|

0.75

|

|

Pirineo-21

|

SB

|

995

|

3.06

|

127

|

19

|

430

|

12.83

|

3.89

|

0.77

|

|

Pirineo-21

|

SB

|

1000

|

4.88

|

98

|

12

|

426

|

18.17

|

4.79

|

0.79

|

|

Pirineo-21

|

SB

|

1020

|

4.24

|

93

|

20

|

425

|

9.83

|

3.94

|

0.71

|

|

Pirineo-21

|

SB

|

1035

|

3.04

|

122

|

12

|

430

|

11.28

|

3.7

|

0.75

|

|

Pirineo-21

|

SB

|

1055

|

3.78

|

118

|

18

|

428

|

22.23

|

4.46

|

0.83

|

|

Pirineo-21

|

SB

|

1060

|

2.89

|

137

|

22

|

429

|

19.63

|

3.95

|

0.83

|

DISCUSSION

Content and origin of preserved organic matter

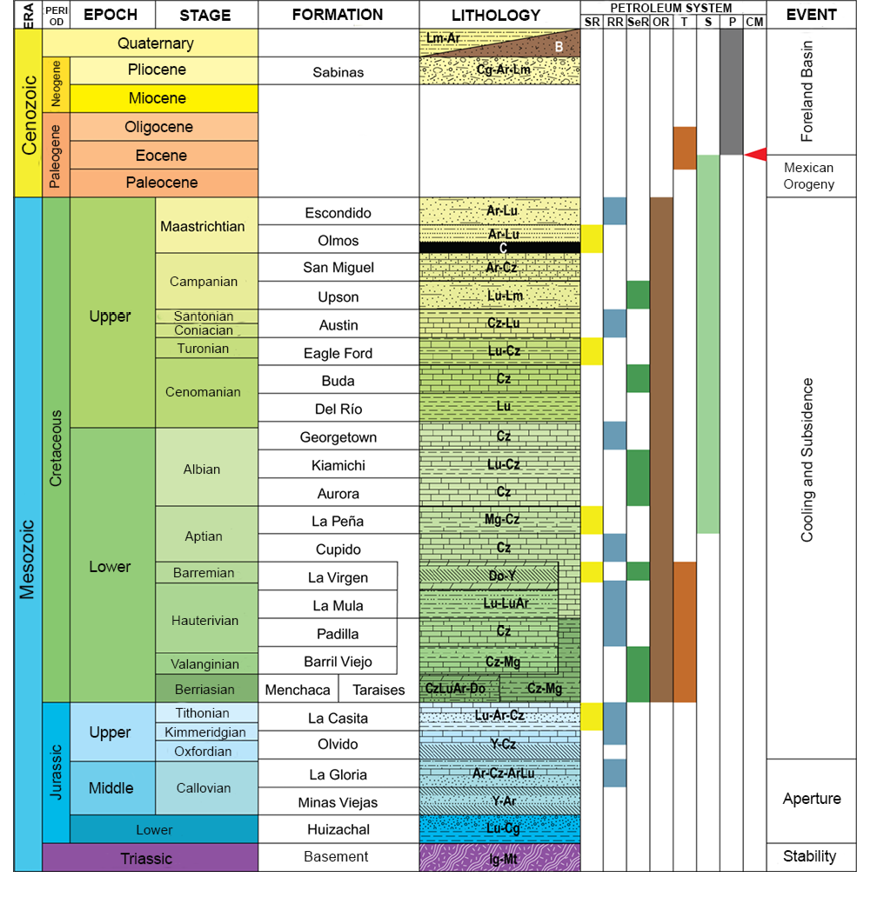

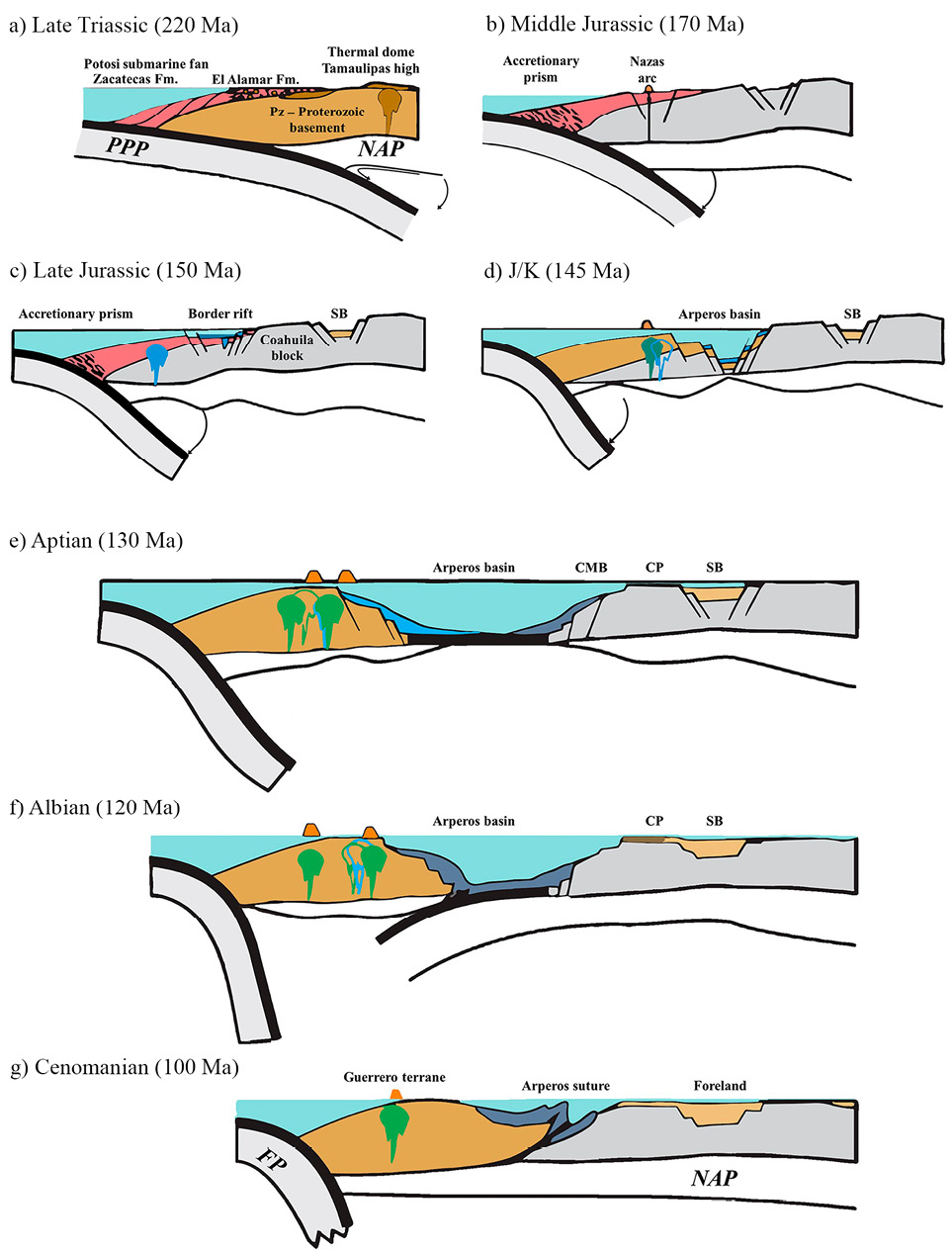

The studied samples of the La Peña Formation have organic richness appropriate for hydrocarbons generation, with poor to excellent source rock potential; according to the classification of Peters and Cassa (1994). The dispersion of the data points in the TOC vs. S2 diagram (Figure 6) and the observed distribution of the TOC content of the La Peña Formation probably reflects different organic-rich levels through this unit, as those described by Barragan (2000). Changes in the intensity of upwelling currents and/or the arrival of continental-derived nutrients linked to climate conditions could explain changes in organic richness, as these processes caused variations in productivity and seafloor redox conditions (Barragan, 2000; Núñez-Useche et al., 2015).

The Tmax vs. HI diagram (Figure 7) exhibits scattered data points indicating the presence of different types of organic matter in the La Peña Formation (kerogen type IV, III and II-III mix). Only two samples are located in the wet/dry gas window, but with low HI content, indicating an inert organic matter. This variable behaviour of kerogen type could be associated with the high rates of continental runoff and nutrients supply occurred during the deposition of the La Peña Formation in the early Aptian (Núñez-Useche, et al., 2014), in addition to paleoenvironmental condition changes during the Early Cretaceous, like transgressive stages associated with global sea level rises, with intercalated periods of different oxygenated conditions and local upwelling systems (Núñez-Useche and Barragán, 2012), resulting in differences in the organic matter composition.

Thermal maturity

The PI vs. Tmax diagram (Figure 8) exhibits variable degree of maturation, ranging from immature to overmature conditions. The samples from the Piedras Negras and the Sabinas basins have different PI values. Some samples from the Sabinas basin possess anomalous high PI values compared to their level of thermal maturity, which suggests that this samples are contaminated with drilling additives or migrated oil (Peters and Cassa, 1994). As with the previous diagram, altogether, these data exhibit a wide range of thermal maturity. According to Hart and Steen, (2015) such a variability may be related to the different thermal maturities areas that the wells come from brought by the different stratigraphic levels where the samples were collected. Furthermore, the pattern of behaviour shown in the PI vs. Tmax diagram may be associated to the existing mix of different types of kerogens at different stratigraphic levels (Akande, 2012) of the La Peña Formation, affecting the performance of the petroleum production during the pyrolysis.

Petroleum Potential

The TOC-HI diagram shows a hydrocarbon generation potential ranging from little or no potential to rich gas prone (Figure 9). These data suggest that the organic matter was thermally altered, reflecting that the samples from the SB reached a greater thermal maturity, allowing them to develop greater gas generation potential, with respect to the samples of the PNB that shows a reduced potential. The decrease of the organic matter maturity towards the NW of the study area may be attributed to different burial degrees related to the combination of different tectonic events of the Mexican Orogeny, which contributed to the cooling of the geological successions, causing erosion and leading to modify the kerogen transformation (Camacho-Ortegón et al., 2017).

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of the Rock-Eval pyrolysis parameters (TOC, Tmax, S1, S2, HI and PI) carried on selected samples from 15 wells in the SB-PNB indicated that: the organic richness of the La Peña Formation varies from poor to excellent, with a petroleum potential (S2 peak) and a TOC content clearly higher for the wells in the SB, compared to the obtained values for the PNB. Similarly, the greater values of free hydrocarbon content (S1 peak) and Production Index (PI) are also observed for the samples of the SB, which indicate its higher hydrocarbon resource potential compared to the La Peña Formation in the PNB. Furthermore, the Rock-Eval data suggest a variability in the thermal maturation for both basins, emphasizing that most of the marginal mature and overmature samples correspond to the SB. On the other hand, the petroleum potential data indicates that the SB samples exhibits a greater gas generation potential, compared to the limited potential given by the HI and TOC content for the PNB samples.

The burial and deposition changing conditions for the La Peña Formation proposed (Barragan, 2000; Barragán, 2001; Núñez-Useche and Barragán, 2012; Núñez-Useche, et al., 2014; Núñez-Useche et al., 2015), could explain the apparent combination of different types of kerogens (III-II, III, IV). However, the results of this work demonstrate that the petroleum potential for the samples is only prone to the gas generation. Furthermore, other types of advanced geochemical and sedimentologic studies should be integrated with the Rock-Eval pyrolysis results in order to obtain a better and complete interpretation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank RMCG reviewers who provided detailed criticisms and suggestions that substantially improved the submitted manuscript.

Special thanks are submitted to the Consejo Estatal de Ciencia y Tecnología (COECYT) through the project COAH-2022-C19-C076.

Also, we would like to express our gratitude to the academic group of the Centro de Investigación en Geociencias Aplicadas - Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila (CIGA–UAdeC) for the collaboration and cooperation shown during the elaboration of this work.

REFERENCES

Akande, W., 2012, Evaluation of Hydrocarbon Generation Potential of the Mesozoic Organic-Rich Rocks Using TOC Content and Rock-Eval Pyrolysis Techniques: Geosciences, 2(6), 164-169, 10.5923/j.geo.20120206.03

Amezcua, N., Rochin, H., Martinez, L.E., 2020, Preliminary strontium isotope stratigraphy of the Jurassic Minas Viejas Formation, in AAPG Hedberg Conference, Geology and Hydrocarbon Potential of the Circum-Gulf of Mexico Pre-salt Section: México, American Association of Petroleum Geologists Hedberg Conference, https://doi.org/10.1306/51652Amezcua2020.

Barragán, R., 2000, Ammonite biostratigraphy, lithofacies variations, and paleoceanographic implications for Barremian-Aptian sequences of northeastern Mexico: Florida International University, Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 1402 DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14050434.

Barragan, R., 2001, Sedimentological and paleocological aspects of the Aptian transgressive event of Sierra del Rosario, Durango, northeast Mexico: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 14, 189-202, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-9811(01)00021-9.

Camacho-Ortegón, L.F., 2009, Origine-Evolution-Migration et Stockage, des hydrocarbures dans le bassin de Sabinas, NE Mexique: étude intégré de pétrographie, géochimie, géophysique et modélisation numérique 1D-2D et 3D : Nancy, France, Université Henri Poincaré, Doctoral Thesis, 388 pp, ⟨NNT : 2009NAN10139⟩, ⟨tel-01748331⟩.

Camacho-Ortegón, L.F., Martínez-Ortegón, L., Pironon, J., Suarez-Ruiz, I., Enciso-Cárdenas, J.J., 2017, Modelado del sistema petrolero de la Cuenca de Sabinas, Noreste de México; Parte 1: evolución térmica, generación y migración de hidrocarburos: Boletín Asociación Mexicana de Geólogos Petroleros, LIX(1), 7-46.

Camacho-Ortegón, L.F., Martínez, L., Enciso-Cárdenas J.J., Bueno-Tokunaga, A., Pironón, J., Núñez-Useche, F., 2022, Thermal history of the Sabinas - Piedras Negras Basin (Northeastern Mexico): Insights from 1D modelling: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 115, 1-14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103756.

Cantú-Chapa, A., 1989, La Peña Formation (Aptian): a condensed limestone-shale sequences from the subsurface of NE Mexico: Journal of Petroleum Geology, 12(1), 69-84, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-5457.1989.tb00221.x.

Charleston, S., 1973, Stratigraphy, tectonics, and hydrocarbon potential of the Lower Cretaceous, Coahuila, Mexico: Ann Arbor, Michigan, University of Michigan, Doctoral Thesis, 268 pp.

Chávez-Cabello, G., 2005, Deformación y magmatismo Cenozoico en el sur de la Cuenca de Sabinas, Coahuila, México: Juriquilla, Querétaro, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro de Geociencias, Ph.D. Thesis, 226 pp.

Chávez-Cabello, G., Aranda-Gómez, J.J., Molina-Garza, R.S., Cossío-Torres, T., Arvizu-Gutiérrez, I.R., González-Naranjo, G.A., 2005, La falla San Marcos: una estructura jurásica de basamento multirreactivada del noreste de México: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 57(1), 27-52.

Chávez-Cabello, G., Aranda-Gómez, J.J., Molina-Garza, R.S., Cossío-Torres, T., Arvizu-Gutiérrez, I.R., González-Naranjo, G.A., 2007, The San Marcos fault: A Jurassic multireactivated basement structure in northeastern México: Geological Society of America, Special Paper, 422, 261-286, https://doi.org/10.1130/2007.2422(08).

Chávez-Cabello, G., Aranda-Gómez, J.J., Iriondo-Perrone, A., 2009, Culminación de la orogenia Laramide en la cuenca de Sabinas, Coahuila, México: Boletín de la Asociación Mexicana de Geólogos Petroleros, 54(1), 78-89.

Davison, I., Pindell, J., Hull, J., 2020, The basins, orogens and evolution of the southern Gulf of Mexico and northern Caribbean: Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 504, 1-27, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP504-2020-218.

De La O-Burrola, F., 2013, Étude pétrographique et géochimique intégrée du charbon et de shale à gaz du bassin Sabinas et de Chihuahua au nord du Mexique : estimation des ressources en gaz méthane: Lorraine, France, Université de Lorraine, Doctoral Thesis, 407 pp. ⟨NNT : 2013LORR0233⟩, ⟨tel-01750526⟩.

De La O-Burrola, F., Martínez, L., Camacho-Ortegón, L.F., Enciso-Cárdenas J.J, 2014, Distribución del Gas metano (CBM y Shale Gas) en las cuencas de Sabinas y Chihuahua, México: Revista Internacional de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (RIIIT), 1(6).

De la Rosa-Rodríguez, G., 2018, Caracterización geoquímica y petrográfica de la Formación Eagle Ford como yacimiento tipo Shale Gas, en la porción central de la Provincia Geológico - Petrolera Sabinas. Nueva Rosita, Coahuila. Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila, Master Thesis, 203 pp.

Eguiluz de Antuñano, S., 2001, Geologic Evolution and Gas Resources of the Sabinas Basin in Northeastern México, in Bartolini, C., Buffler, R. T., Cantú-Chapa, A. (eds.), The western Gulf of México Basin: Tectonics, sedimentary basins, and petroleum systems: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoir, 75, 241-270, https://doi.org/10.1306/M75768C10.

Eguiluz de Antuñano, S., 2011, Secuencias estratigráficas del Berriasiano-Aptiano en la Cuenca de Sabinas: su significado en el entendimiento de la evolución geológica del noreste mexicano: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 63(2), 285-311.

Eguiluz de Antuñano, S., Amezcua-Torres, N., 2003, Coalbed methane resources of the Sabinas Basin, Coahuila, México: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Memoir, 79, 395-402.

Eguiluz de Antuñano, S., Chávez-Cabello, G., 2022, Extensión sinsedimentaria del Cretácico Inferior en el borde del Bloque Coahuila, un margen tipo rift en México: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 74(1), A130821, http://dx.doi.org/10.18268/BSGM2022v74n1a130821.

Eguiluz de Antuñano, S, Aranda-García, M., Marrett, R., 2000, Tectónica de la Sierra Madre Oriental, México : Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 53(1), 1-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.18268/BSGM2000v53n1a1.

Enciso-Cárdenas, J.J., Núñez-Useche, F., Camacho-Ortegón, L.F., de la Rosa-Rodríguez, G., Martínez-Yáñez, M., Gómez-Borrego, A., 2021, Paleoenvironment and source-rock potential of the Cenomanian-Turonian Eagle Ford Formation in the Sabinas basin, northeast Mexico: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 108, 1-14, DOI 10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103184.

Espitalié, J., Madec, M., Tissot, B., Mennig, J.J., Leplat, P., 1977, Source rock characterization method for petroleum exploration, in Annual Offshore Techn. Conference, 9th, Proceedings, 439-444.

Espitalié, J., Deroo, G., Marquis, F., 1985, Rock-Eval pyrolysis and its applications: Revue de l’Institut Francais du Petrole, 40, 755-784, https://doi.org/10.2516/ogst:1985045.

Fitz-Diaz, E., van der Pluijm, B., 2013, Fold dating: A new Ar/Ar illite dating application to constrain the age of deformation in shallow crustal rocks: Journal of Structural Geology, 54, 174-179, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2013.05.011.

Fitz-Díaz, E., Hudleston, P., Kirschner, D., Siebenaller, L., Camprubí, T., Tolson, G., PiPuig, T., 2011, Insights into fluid flow and water-rock interaction during deformation of carbonate sequences in the Mexican foldthrust belt: Journal of Structural Geology, 33, 1237-1253, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2011.05.009.

Fitz-Díaz, E., Lawton, T.M., Juárez-Arriaga, E., Chávez-Cabello, G., 2018, The Cretaceous-Paleogene Mexican orogen: Structure, basin development, magmatism and tectonics: Earth-Science Reviews, 183, 56-84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.03.002.

Goldhammer, R.K., 1999, Mesozoic sequence stratigraphy and paleogeographic evolution of northeast of Mexico, in Bartolini, C., Wilson, J.L., Lawton, T.F., (eds.), Mesozoic Sedimentary and Tectonic History of North-Central Mexico: Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of North America Special Paper, 340, 1-58.

Goldhammer, R.K., Johnson C.A., 2001, Middle Jurassic-Upper Cretaceous paleogeographic evolution and sequence-stratigraphic framework of the northwest Gulf of Mexico rim, in Bartolini, C., Buffler, R.T., Cantú-Chapa, A. (eds.), The western Gulf of Mexico Basin: Tectonics, sedimentary basins, and petroleum systems: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Memoir 75, 45-81, https://doi.org/10.1306/M75768.

Goldhammer, R.K., Lehmann, P.J., Todd, R.G., Wilson, J.L., Ward, W.C., Johnson, C.R., 1991, Sequence stratigraphy and cyclostratigraphy of the Mesozoic of the Sierra Madre Oriental, northeast Mexico, a field guidebook: Gulf Coast Section, Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, 85 pp.

Goldhammer, R.K., Dunn, P.A., Lehmann, P.J., 1993, The origin of high frequency platform carbonate cycles and third-order sequences (Lower Ordovician El Paso Group, west Texas): Constraints from outcrop data, inverse and forward stratigraphic modelling: Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 63, 318359.

González-Betancourt, A.Y., González-Partida, E., Piedad-Sánchez, N., Carrillo-Chávez, A., González-Ruiz, L.E., González-Ruiz. D., 2020, Diagénesis de la Formación Eagle Ford y sus marcadores térmicos como productora de gas no convencional: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 72(2), 1-24, http://dx.doi.org/10.18268/BSGM2020v72n2a151219.

González-Partida, E., González-Ruiz, L.E., Pironon, J., Romero-Rojas, M.C., González-Betancourt, A.Y., 2016, Potencial Energético del NE de México a partir de la evolución térmica de las cuencas de Sabinas-Chihuahua, en XXVI Congreso Nacional de Geoquímica: Morelia, Mich., Mexico, Actas INAGEQ, 22, p. 233.

González-Partida, E., Piedad Sánchez, N., González Betancourt A., González Ruiz, D., González Sánchez, F., González Ruiz, L., 2017, Estado actual del conocimiento para el estudio de la historia térmica de cuencas y sus procesos diagenéticos: Una revisión de los métodos más aplicados, in memorias del XVII Congreso Nacional de Geoquímica: Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico, Actas INAGEQ, 13(1), 209-222.

González-Partida E., Sánchez, F., González-Carrillo, Piedad Sánchez, N., 2020, Procesos diagenéticos e historia térmica de los mantos de carbón con potencial de gas (CBM) en la Cuenca de Sabinas: Sub-Cuencas Sabinas, Las Esperanzas y Saltillito-Lampacitos, in Memoria del XXX Congreso Nacional de Geoquímica: Chihuahua, Chi., Mexico, Actas INAGEQ 2020, 26, 130-131.

González-Partida, E., González-Betancourt, A.Y., Camprubí, A., Carrillo-Chávez, A., Iriondo, A., Enciso-Cárdenas, J.J., González Carrillo, F., Vázquez Ramírez, J.T., 2022, Tiempos de Acumulación de Carbón en México con especial énfasis en la Cuenca de Sabinas México, donde se proporcionan nuevos datos geocronológicos: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 39, 293-307, doi:10.22201/cgeo.20072902e.2022.3.1704.

González-Sánchez, F., Puente-Solís, R., González-Partida, E., Camprubí, A., 2007, Estratigrafía del Noreste de México y su relación con los yacimientos estratoligados de fluorita, barita, celestina y Zn-Pb: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 59, 43-62.

González-Sánchez, F., Camprubí, A., González-Partida, E., Puente-Solís, R., Canet, C., Centeno- García, E., Atudorei, V., 2009, Regional stratigraphy and distribution of epigenetic stratabound celestine, fluorite, barite and Pb-Zn deposits in the MVT province of northeastern Mexico: Mineralium Deposita, 44, 343-361.

Gray, G.G., Lawton, T.F., 2011, New constraints on timing of Hidalgoan (Laramide) deformation in the Parras and La Popa basins, NE Mexico: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 63, 333-343, https://doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2011v63n2a13.

Gray, G.G., Villagomez, D., Pindell, J., Molina-Garza, R., O’Sullivan, P., Stockli, D., Farrell, W., Blank, D., Schuba, J., 2020, Late Mesozoic and Cenozoic thermotectonic history of eastern, central and southern Mexico as determined through integrated thermochronology, with implications for sediment delivery to the Gulf of Mexico: Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 504, 255-283, https://doi.org/10.1144/sp504-2019-243.

Hart B.S., Steen A.S., 2015, Programmed pyrolysis (Rock-Eval) data and shale paleoenvironmental analyses: A review: Interpretation 3, SH41-SH58, https://doi.org/10.1190/INT-2014-0168.1.

Humphrey, W.E., 1949, Geology of the Sierra de los Muertos area, Mexico (with Descriptions of Aptian Cephalopods from the La Peña Formation): Geological Society of America Bulletin,60, 89-176, https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1949)60[89:GOTSDL]2.0.CO;2.

Imlay, R., 1936, Geology of the western part of the Sierra de Parras. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 47, 1091-1152, https://doi.org/10.1130/GSAB-47-1091.

Juárez-Arriaga, E., Lawton, T.F., Stockli, D.F., Solari, L., Martens, U., 2019a, Late Cretaceous-Paleocene stratigraphic and structural evolution of the central Mexican fold and thrust belt, from detrital zircon (UTh)/(He-Pb) ages: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 95, 102264 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2019.102264.

Karg, H., Littke R., 2020, Tectonic control on hydrocarbon generation in the northwestern Neuquén Basin, Argentina: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Memoir 104(10), 2173-2208. https://doi.org/10.1306/05082018171.

Katz, B.J., 1983, Limitations of ‘Rock-Eval’ pyrolysis for typing organic matter: Organic Geochemistry, 4, 195-199, doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(83)90041-4.

Longoria, F.J., 1984, Stratigraphic studies in the Jurassic of North–eastern Mexico: Evidence for the origin of Sabinas basin, in the Jurassic of the Gulf Rim, Gulf Coast Section: Washington, USA, Society for Sedimentary Geology, 171-193, https://doi.org/10.5724/gcs.84.03.0171.

Martínez, L., Camacho, L.F., Piedad-Sánchez, N., González-Partida, E., Suárez- Ruiz, I., Enciso, J., 2015, Entorno diagenético en el Bloque Pirineo, Cuenca de Sabinas, México: Interacción agua-roca-hidrocarburo: Revista Internacional de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica 13, 2-32.

McKee, J.W., Jones, N.W., Long, L.E., 1984, History of recurrent activity along a major fault in northeastern Mexico: Geology, 12, 103-107.

Menetrier, C., 2005. Modélisation Thermique Applique aux Bassins Sédimentaires: Basin de Paris (France) et Basin de Sabinas (Mexique): Nancy, France, Université Henri Poincaré, Doctoral Thesis, 268 pp, ⟨NNT : 2005NAN10205⟩, ⟨tel-01746518⟩.

Molina-Garza, R.S., Chávez-Cabello, G., Iriondo, A., Porras-Vázquez, M.A., Terrazas-Calderón, G.M., 2008, Paleomagnetism, structure and 40Ar/39Ar geochronology of the Cerro Mercado pluton, Coahuila: Implications for the timing of the Laramide orogeny in northern Mexico: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 25(2), 284-301.

Núñez-Useche, F., Barragán, R., 2012, Microfacies analysis and paleoenvironmental dynamic of the Barremian-Albian interval in Sierra del Rosario, eastern Durango state, Mexico: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 29(1), 204-218.

Núñez-Useche, F., Barragán, R., Moreno-Bedmar, J. A., Canet, C., 2014, Mexican archives for the major Cretaceous Oceanic Anoxic Events: Boletín de La Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 66(3), 491-505, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24921297

Núñez-Useche, F., Barragán, R., Moreno-Bedmar, J.A., Canet, C., 2015, Geochemical and paleoenvironmental record of the early to early late Aptian major episodes of accelerated change: evidence from Sierra del Rosario, Northeast Mexico: Sedimentary Geology, DOI: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2015.04.006.

Obregón-Andría, L., Muñoz-Loredo, G., 1988, Evolución de los carbones de Coahuila: Ciencia y Desarrollo, 79 (14), 71-81.

Ortega-Lucach, S., Gutierrez-Caminero, L., Torres-Vargas, R., Murillo-Muñetón, G., 2018, Geochemical characterization of the eagle Ford formation in northeast Mexico, in Unconventional Resources Technology Conference: Houston, Texas, Society of Exploration Geophysicists, American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 184-187, https://doi.org/10.15530/urtec-2018-2887535.

Padilla y Sánchez, R.J., 1986, Post-paleozoic tectonics of Northeast Mexico and its role in the evolution of the Gulf of Mexico: Geofisica Internacional, 25(1), 157-206, https://doi.org/10.22201/igeof.00167169p.1986.25.1.804.

Perelló, J., 2021, Geologic observations in the San Marcos area, Coahuila, Mexico: the case for sediment-hosted stratiform copper-silver mineralization in the Sabinas basin during the Laramide orogeny: Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 73(3), 00019, https://doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2021v73n3a160321.

Peters, K.E., Cassa, M.R., 1994, Applied Source Rock Geochemistry: Chapter 5, in Magoon L.B., Dow, W.G. (eds.), The petroleum system–from source to trap: AAPG Memoir 60, 93-120.

Petróleos Mexicanos, 2012, Situación Actual y Perspectivas de PEMEX, in Expo foro 2013, México, D.F., 1-8.

Piedad-Sánchez, N., 2004, Prospection des hydrocarbures par une approche intégrée de petrographie, géochimie et modélisation de la transformation de la matière organique: Analyse et reconstitution de l’histoire thermique des Bassins Carbonifère Central des Asturies (Espagne) et Sabinas-Piedras Negras (Coahuila, Mexique): France, Université de Lorraine, Doctoral Thesis, 356 pp, ⟨NNT : 2004NAN10155⟩.

Piedad-Sánchez, N., Suárez-Ruiz, I., Martínez, L., Izart, A., Elie, M., Keravis, D., 2005a, Organic petrology and geochemistry of the Carboniferous coal seams from the Central Asturian Coal Basin (NW Spain): International Journal of Coal Geology, 57, 211-242.

Piedad-Sánchez, N., Martinez L., Garza Blakaller C., 2005b, Estudio de la Industria del Carbón en la Región Carbonífera del Estado de Coahuila y del cluster del carbón a nivel mundial: Corporación Mexicana de Investigación en Materiales, S.A., 16-29.

Piedad-Sánchez, N., Martínez, L., Suárez-Ruiz, I., Alsaab, D., Izart, A., Milenkova, K., 2005c, Estudio preliminar de la estructura del carbón de la Formación Olmos en la Región Carbonífera, Coahuila, México, en Convención Internacional de Minería XXVI: Veracruz, Ver., Mexico, Acta de Sesiones, 89-90.

Pindell, J.L., 1985, Alleghenian reconstruction and subsecuent evolution of the Gulf of Mexico, Bahamas, and Proto-Caribbean: Tectonics 4, 1-39.

Pindell, J.L., 1993, Regional synopsis of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean evolution, in Pindell, J.L., Perkins, B.F., (eds.), Mesozoic and early Cenozoic development of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean region: Gulf Coast Section, SEPM (Society for Sedimentary Geology), Foundation, 13th Annual Research Conference, 251-274.

Pindell, J.L., Dewey, J.F., 1982, Permo-Triassic reconstruction of western Pangea and the evolution of the Gulf of Mexico/Caribbean region: Tectonics, 1, 179-212, https://doi.org/10.1029/TC001i002p00179.

Pindell, J., Villagómez, D., Molina-Garza, R., Graham, R., Weber, B., 2020, A revised synthesis of the rift and drift history of the Gulf of Mexico and surrounding regions in the light of improved age dating of the Middle Jurassic salt: Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 504, 29-76, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP504-2020-43.

Ramírez-Peña, C.F., Chávez-Cabello, G., 2017, Age and evolution of thin-skinned deformation in Zacatecas, Mexico: Sevier orogeny evidence in the Mexican foldthrust belt: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 76, 101-114, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2017.01.007.

Salvador, A., 1987, Late Triassic-Jurassic paleogeography and origin of Gulf of Mexico basin: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 71, 419-451.

Salvador, A., 1991a, The Gulf of Mexico basin: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society of America, Geology of North America, vol. J, 568 pp.

Salvador, A., 1991b, Triassic-Jurassic, in Salvador, A. (ed.), The Gulf of Mexico Basin: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society of America, Geology of North America, vol. J, 131-180.

Salvador, A., 1991c, Origin and development of the Gulf of Mexico basin, in Salvador, A., (ed.), The Gulf of Mexico basin: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society of America, Geology of North America, vol. J, 389-444.

Santamaría-Orozco, O.D., Ortuño, A.F., Adatte, T., Ortiz, U.A., Riba, R.A., Franco, N.S., 1991, Evolución geodinámica de la Cuenca de Sabinas y sus implicaciones petroleras, Estado de Coahuila, México: México, D.F., Instituto Mexicano del Petróleo, Tomo 1, 210 pp.

Stevens, S.H., Moodhe K.D., 2015, Evaluation of Mexico's Shale Oil and Gas Potential, in SPE Latin American and Caribbean Petroleum Engineering Conference: Quito, Ecuador, https://doi.org/10.2118/177139-MS.

Williams, S.A., Singleton, J.S., Prior, M.G., Mavor, S.P., Cross, G.E., Stockli, D.F., 2020, The early Palaeogene transition from thin-skinned to thick-skinned shortening in the Potosí uplift, Sierra Madre Oriental, northeastern Mexico: International Geology Review, 63(2), 233-263, https://doi.org/10.1080/00206814.2020.1805802.